I spent Memorial Day week down in the Outer Banks (“OBX”) of North Carolina, with my husband and our dogs, my sister-in-law, and my younger two kids—including the youngest of my four children, my son who just graduated from William & Mary summa cum laude with a double major in economics and business analytics (#proudmama). My daughter brought along her boyfriend, and my son brought along his girlfriend plus 13 more of his teammate friends from the W&M track team, making this first “post-pandemic” beach week for our family also a graduation present to my son.

The vacation turned out to be a learning trip for me, not because I was trying to make it one, but just because it happened that way. Below are a few things my week at the beach told me about what’s been special about all of us living through the pandemic year and how we’re starting to emerge on the other side. The pandemic recession was not just disruptive but enlightening and transformational for the U.S. economy, because of the changes people have made in their lives, and the inability or lack of desire to just get back to the way things were. The OBX provides a vivid illustration, because it is so specialized in certain kinds of economic activity and is geographically isolated (difficult to get to).

Work v. Life became Work & Life. In the OBX, vacation homes have been nearly fully booked up since they reopened last May, even back when local leisure and hospitality business operations were still greatly restricted. With work and school no longer “place based” for many Americans, families were forced to manage on their own under their own roofs, and while some struggled to make it work, others thrived. Collecting usual salaries while avoiding the usual commuting and child care costs, some families had the financial means to move out of their smaller dwellings in the cities to larger homes further out. Even if family-centered “pod” life might have been stressful at first, as the pandemic wore on, many people have decided they like being able to better combine their work with the rest of their lives. Even when offices and schools are fully reopened, it’s not likely that everyone will go back to their pre-pandemic office and school settings.

Leisure/Hospitality jobs disappeared, and the workers moved on. The OBX completely shut down to non-owner visitors at the start of the pandemic, for two months from mid-March to mid-May 2020. Even when they reopened to non-owner visitors in May 2020 (and my family traveled down there at that first opportunity), the few restaurants that had reopened were only offering takeout, as business restrictions dictated. Workers who lost their jobs here had no choice but to go on unemployment, or to move to other places and other kinds of work. The longer the pandemic continued, the more likely it became that OBX leisure/hospitality businesses lost their connections to their previous employees and would not be able to just “call them back” once the pandemic was over. And so it goes in the OBX this summer: restaurants can now operate at full capacity, but they don’t have the staff to handle their usual summer-season volume. The short supply of workers in the OBX is due to both: (i) a lack of an adequate number of “home-grown” workers (there are hardly any young people best suited for leisure/hospitality jobs who live full time in the OBX), and (ii) the ongoing suspension of the temporary work/visit visa programs which bring young worker-visitors over from other countries and are how beach resort areas would normally match the summer surges in demand.

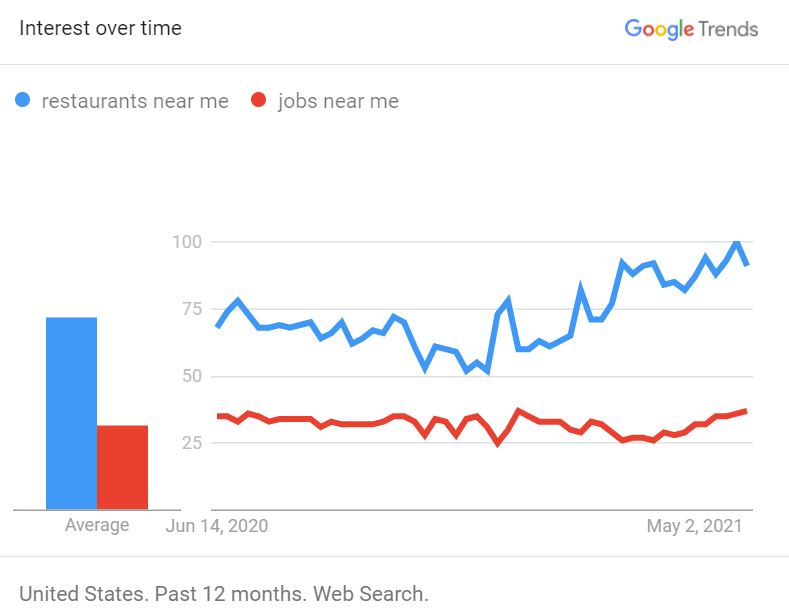

The unleashing of the “cooped-up demand” for going out is happening all over. It’s not just the OBX that is currently experiencing a “supply chain” problem of demand for labor outpacing supply of labor in the leisure/hospitality sector. Locationally-precise Google Trends data illustrate this is happening across the country as a whole, with searches for “restaurants near me” accelerating well ahead of searches for “jobs near me” over the past few months as vaccination rates rose and business restrictions lifted.

(I’m going to elaborate on this simple indicator of labor demand vs. supply by looking more closely at (and sharing) these trends in Google searches from different local parts of the country in the next couple weeks. The “ground-level” stories are revealing about the “why” these labor shortages and the challenges to alleviating them.)

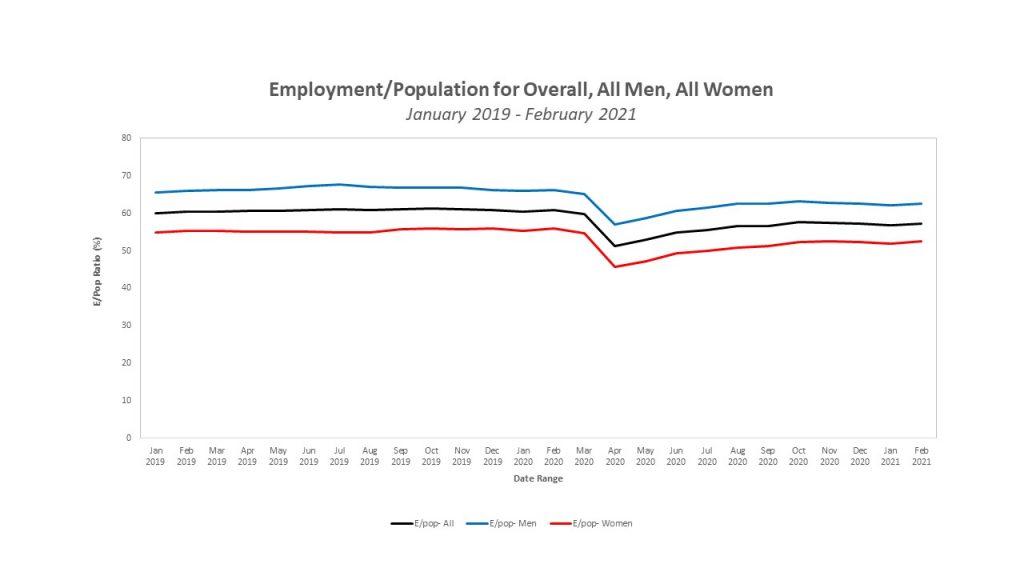

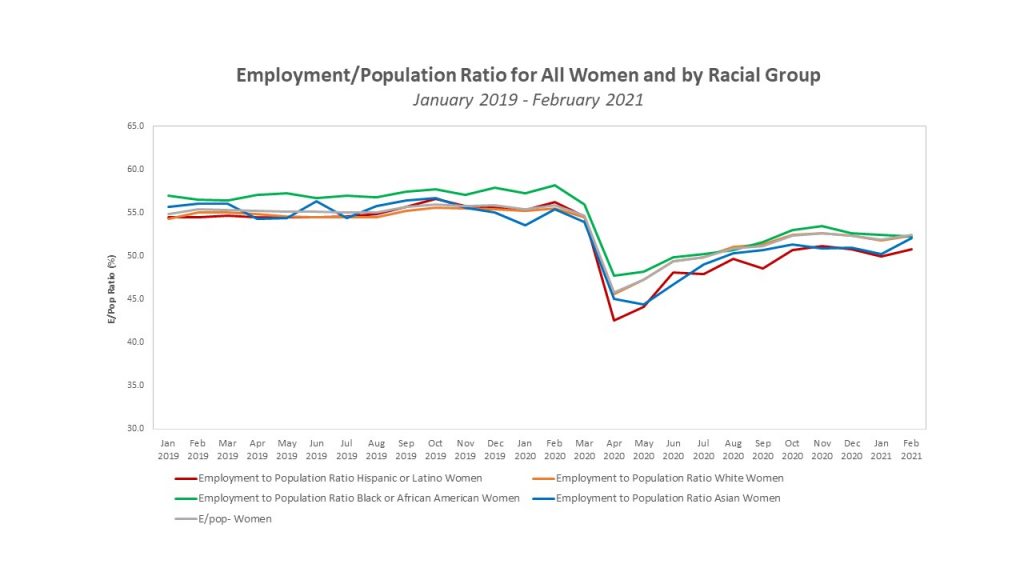

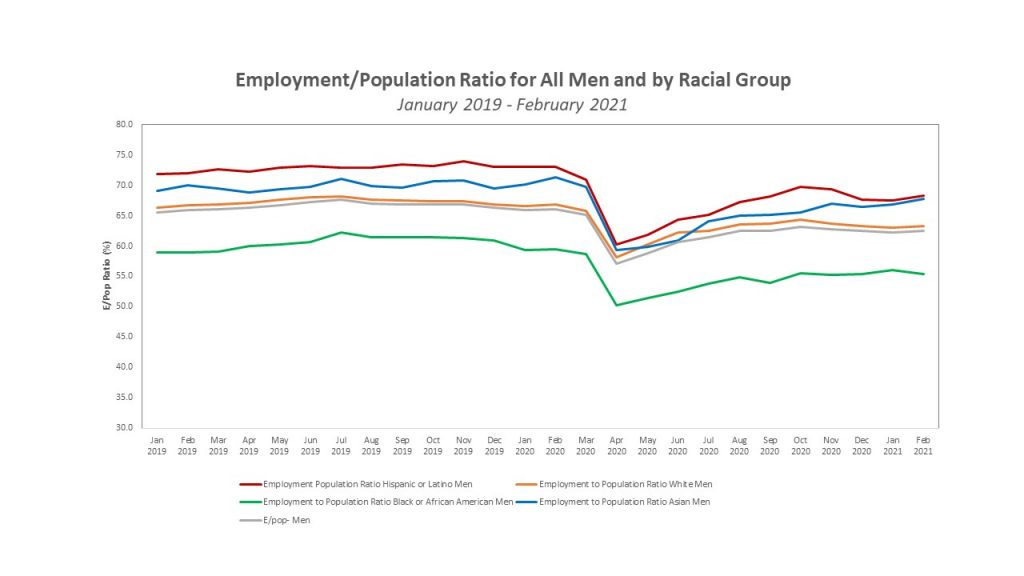

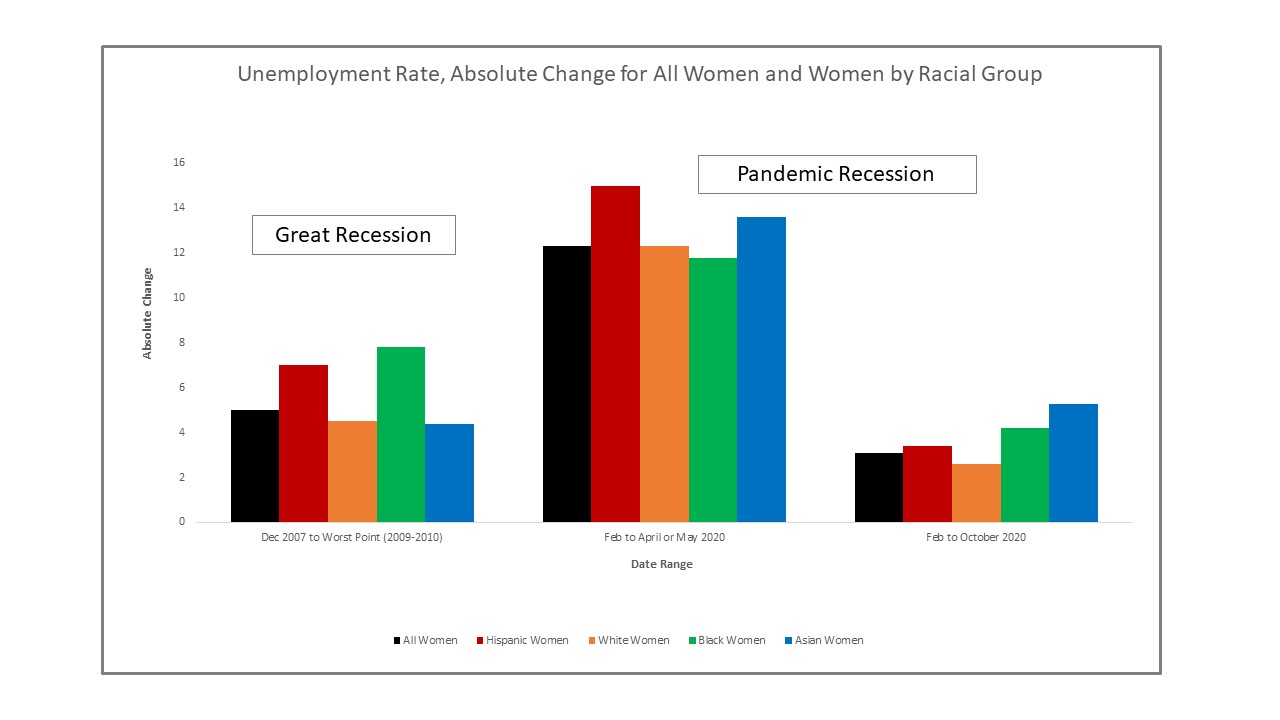

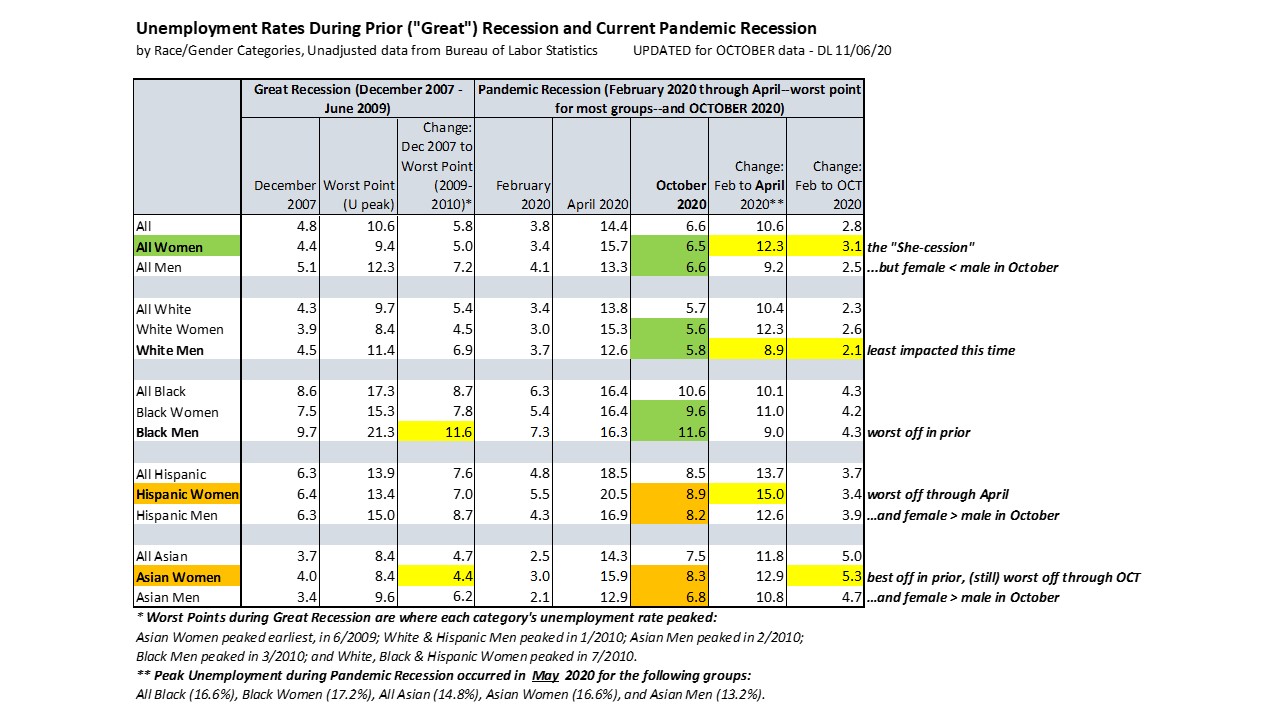

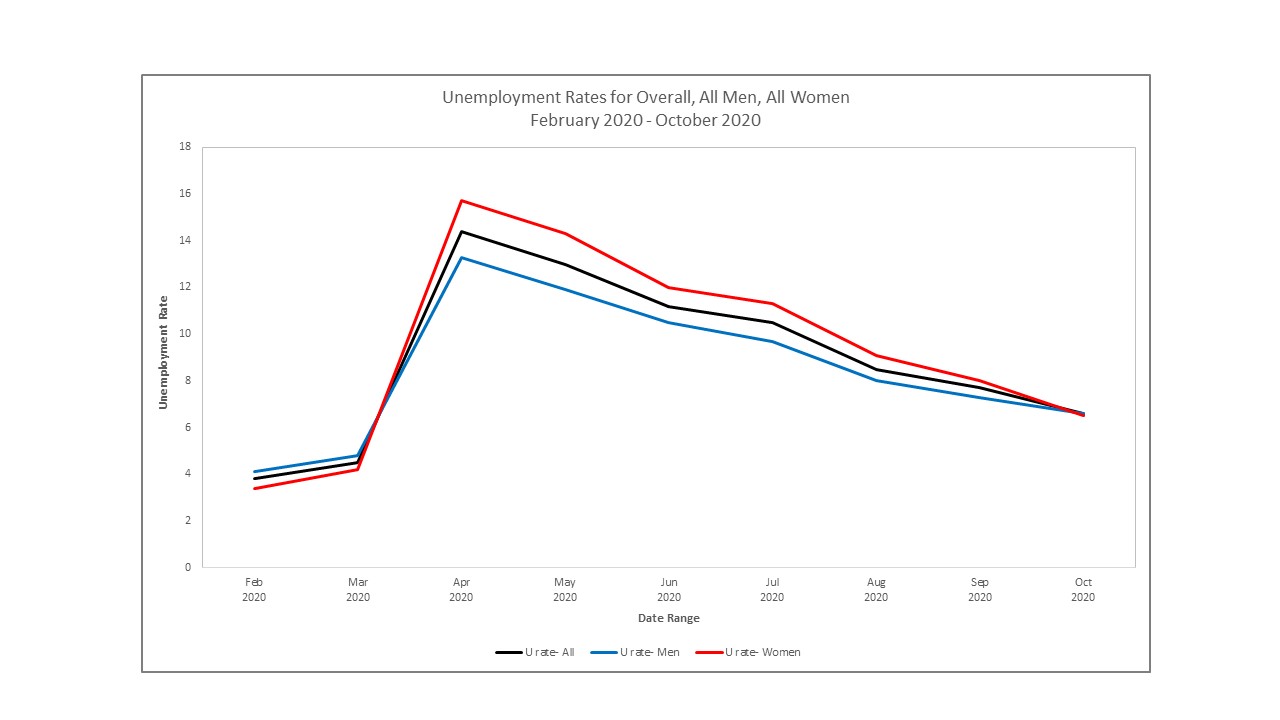

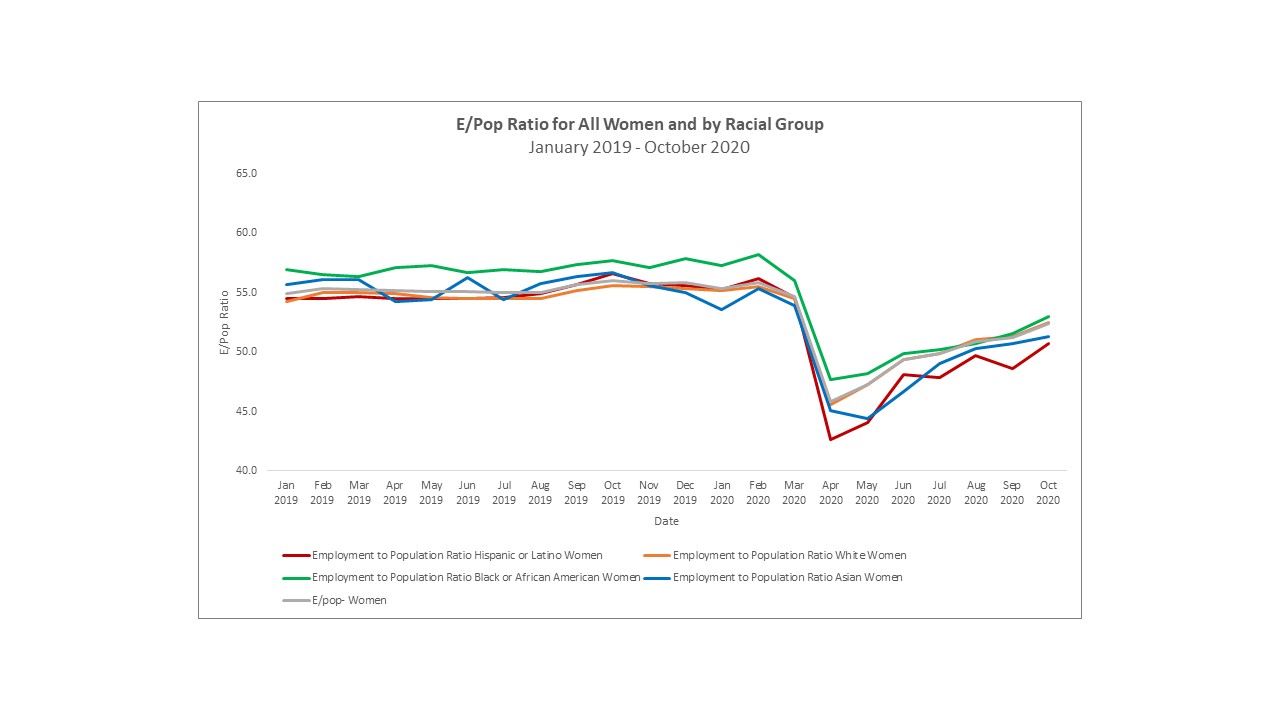

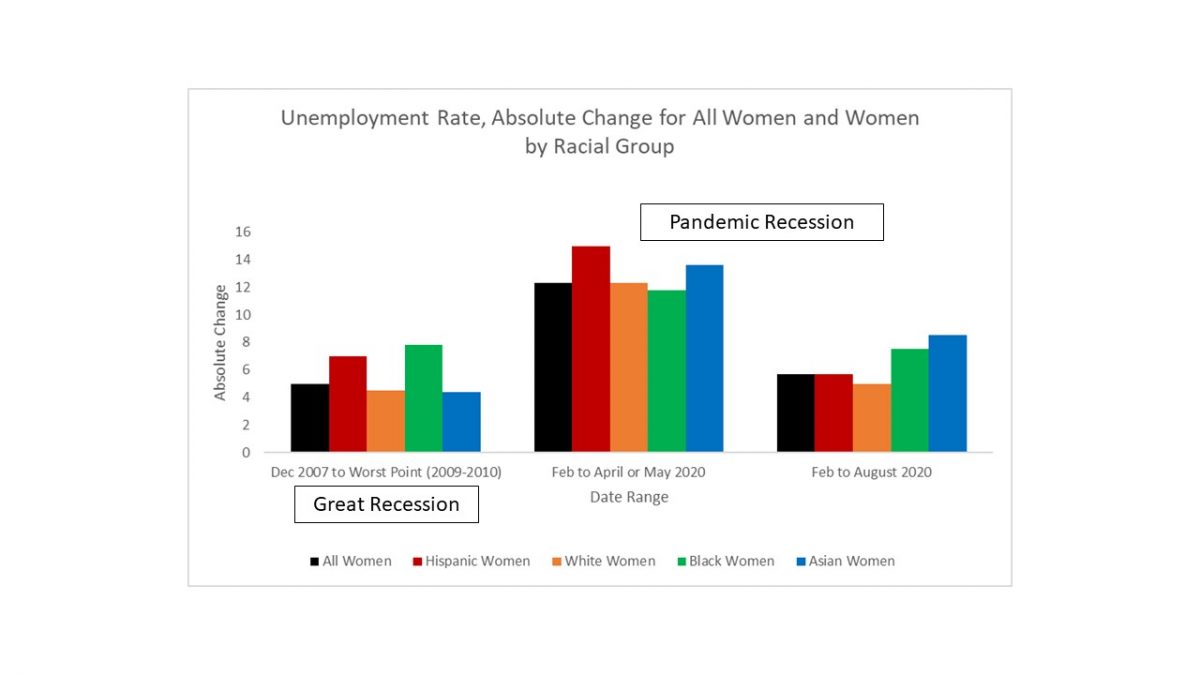

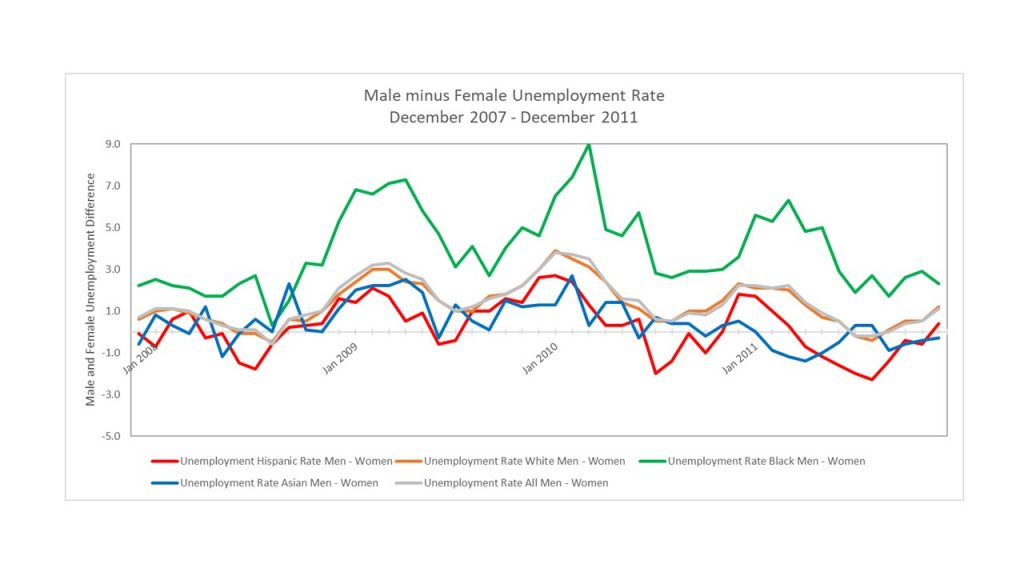

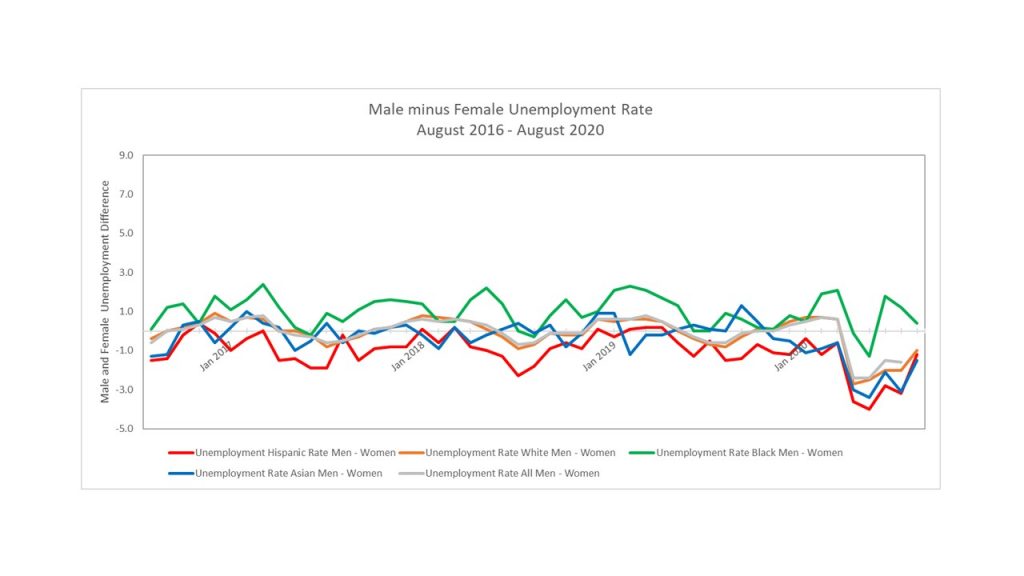

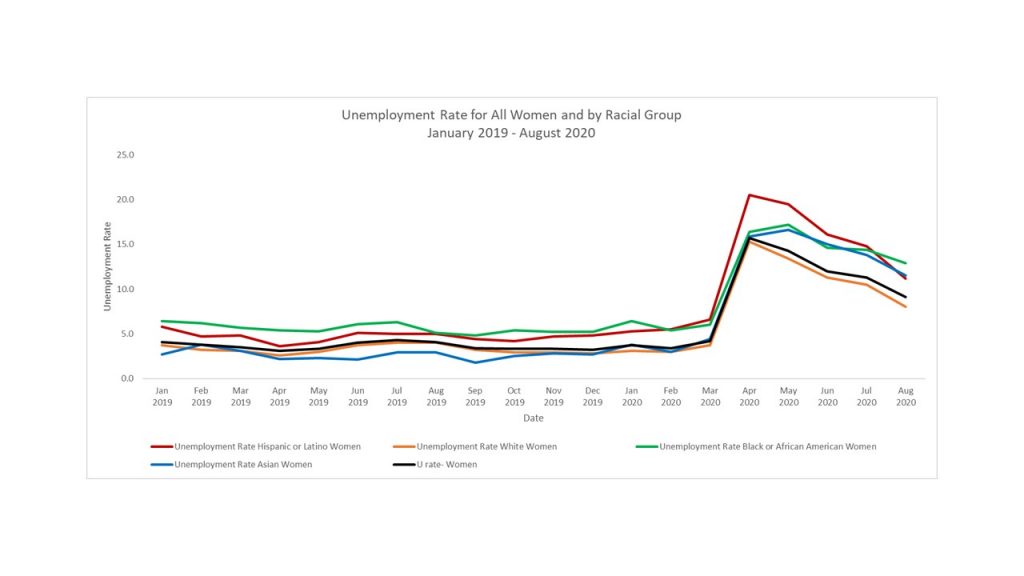

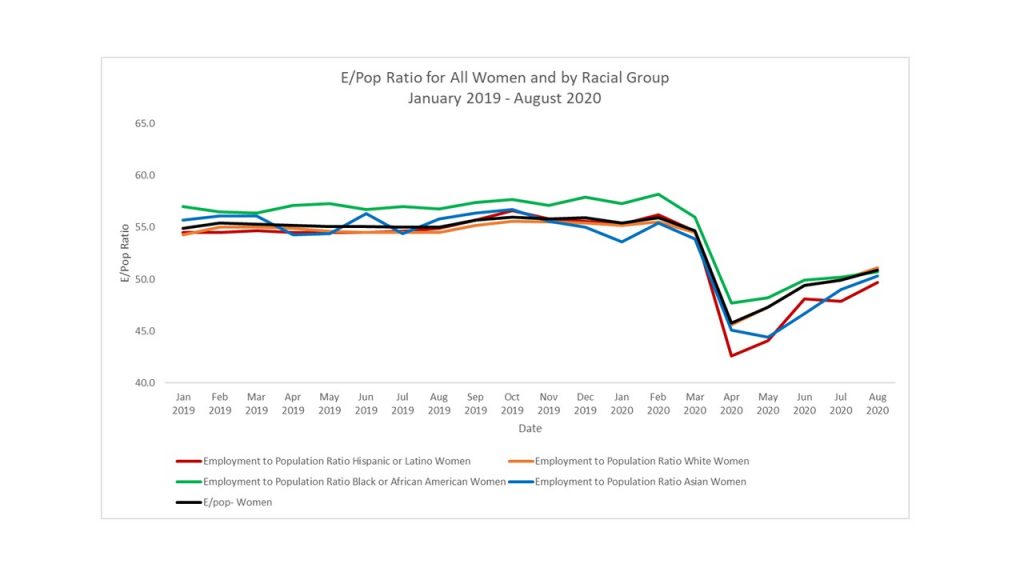

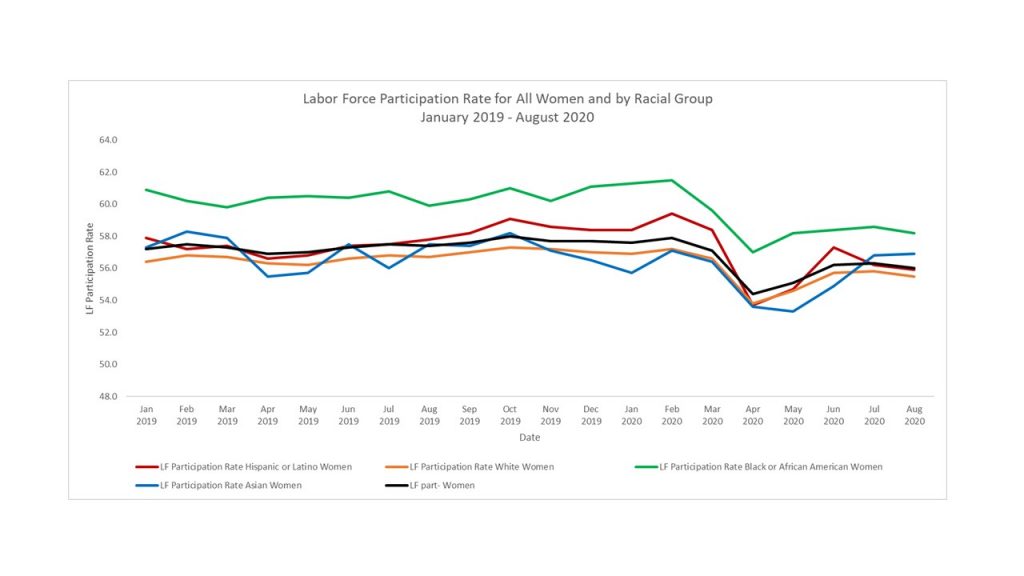

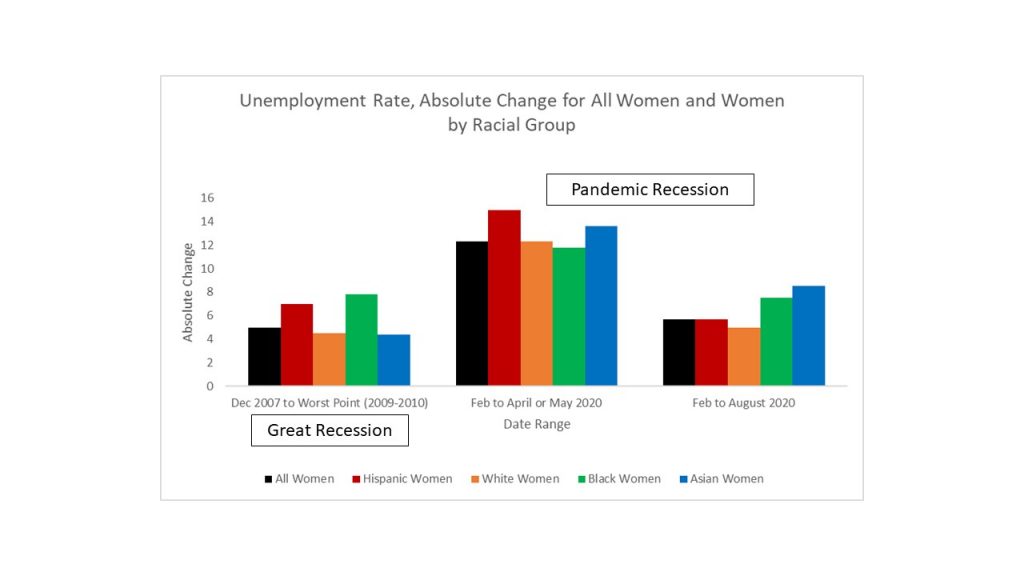

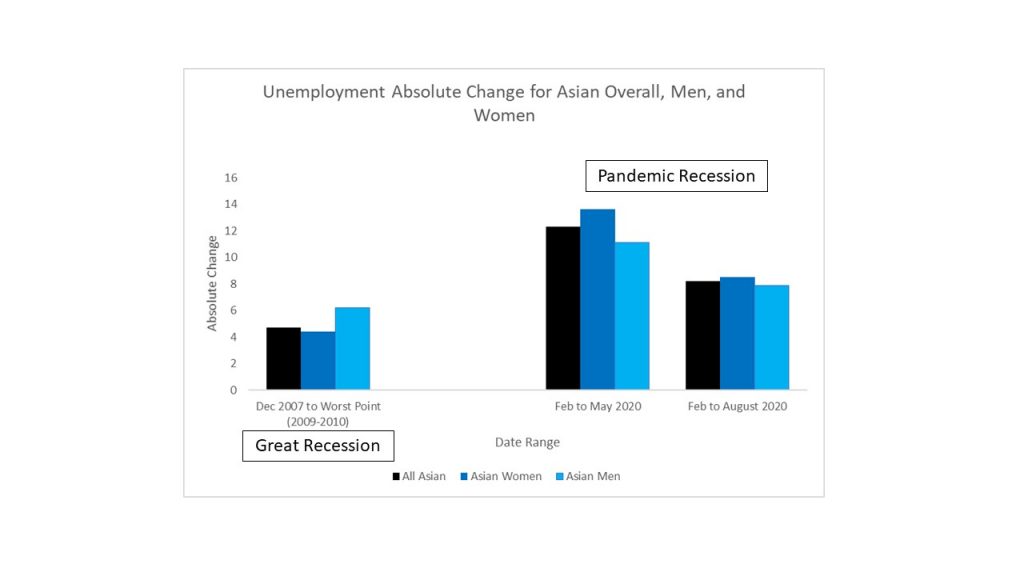

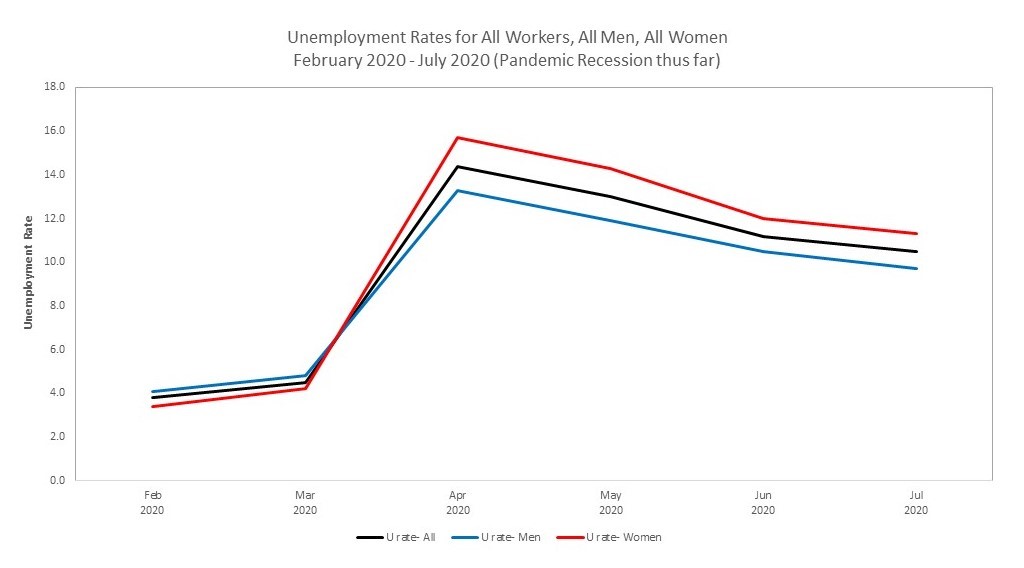

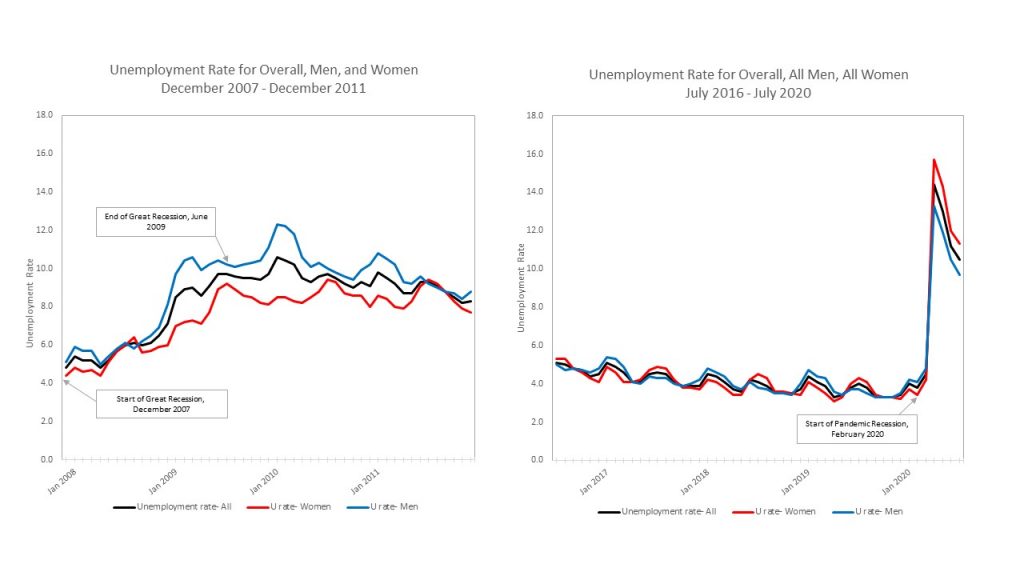

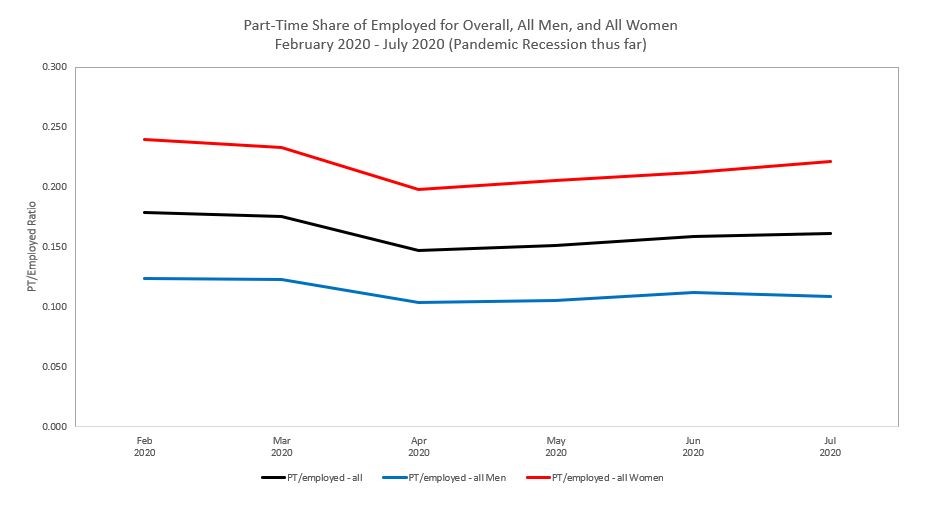

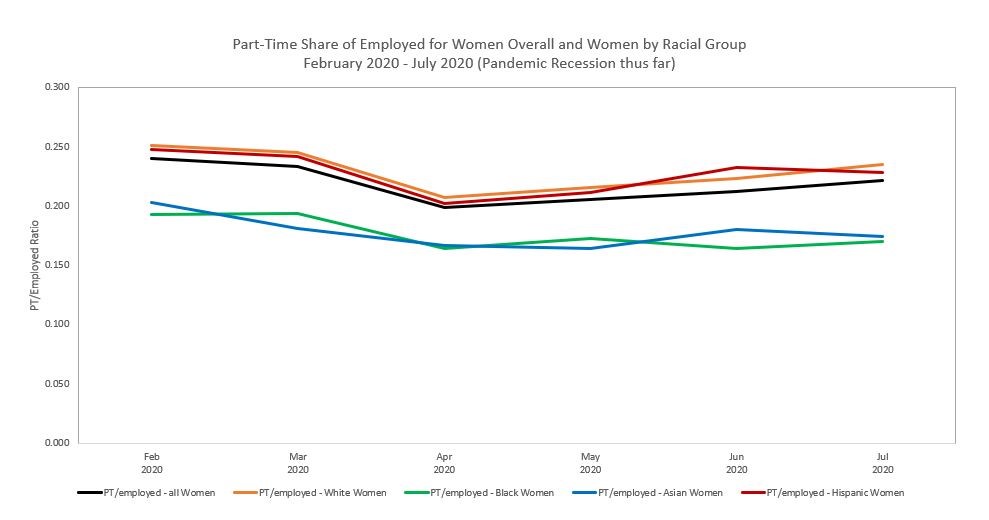

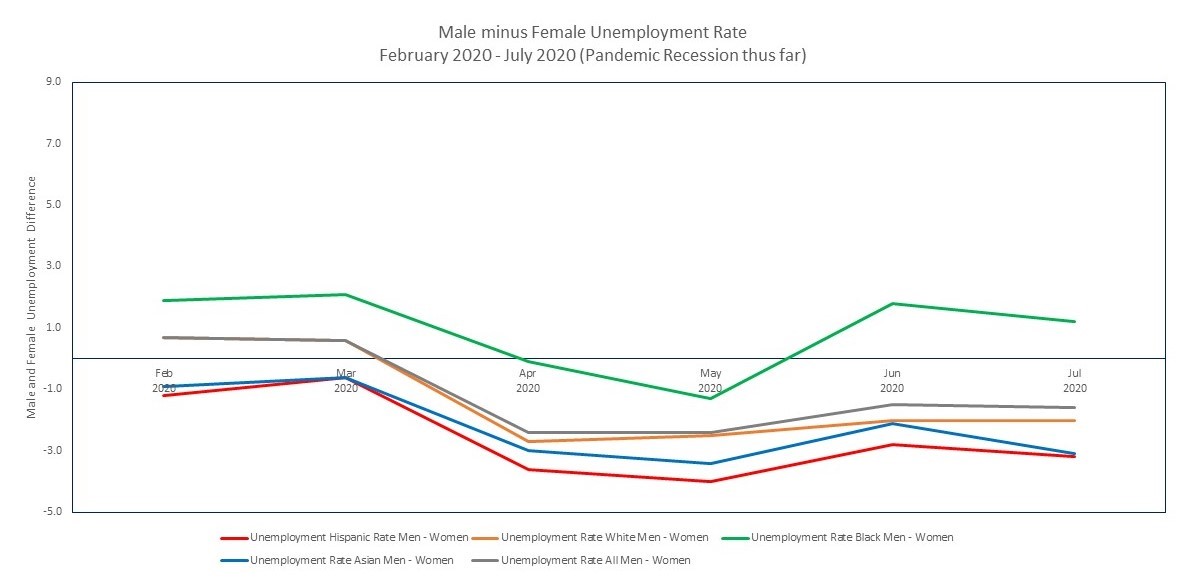

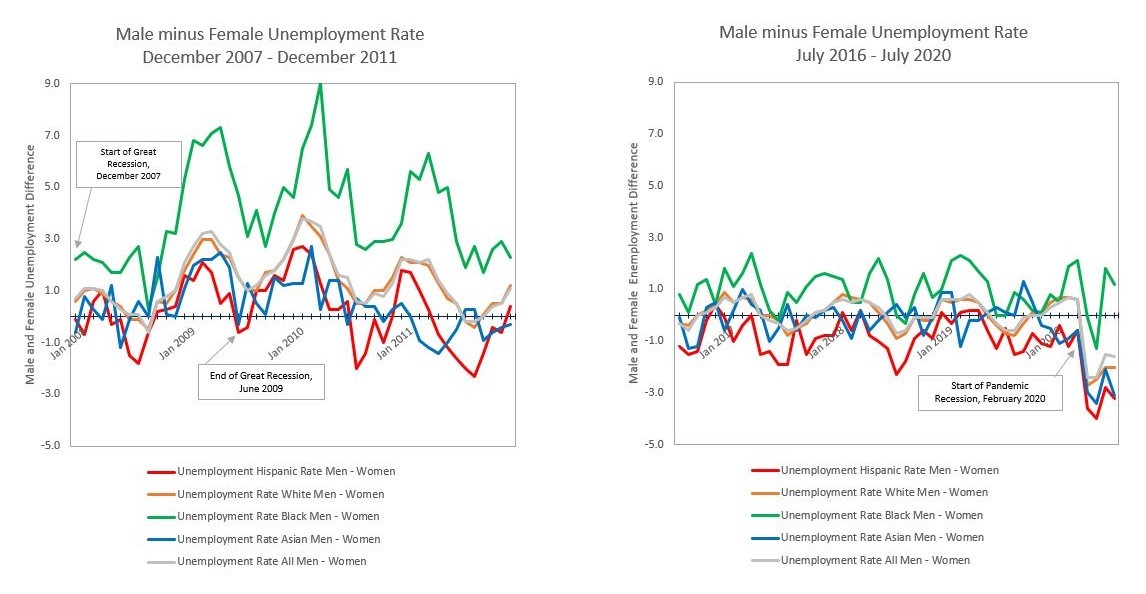

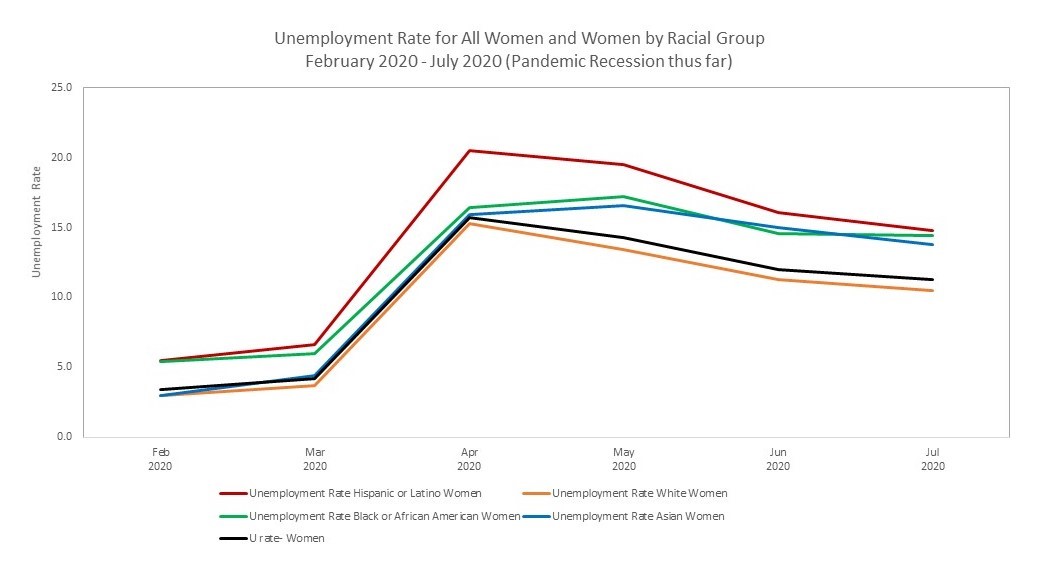

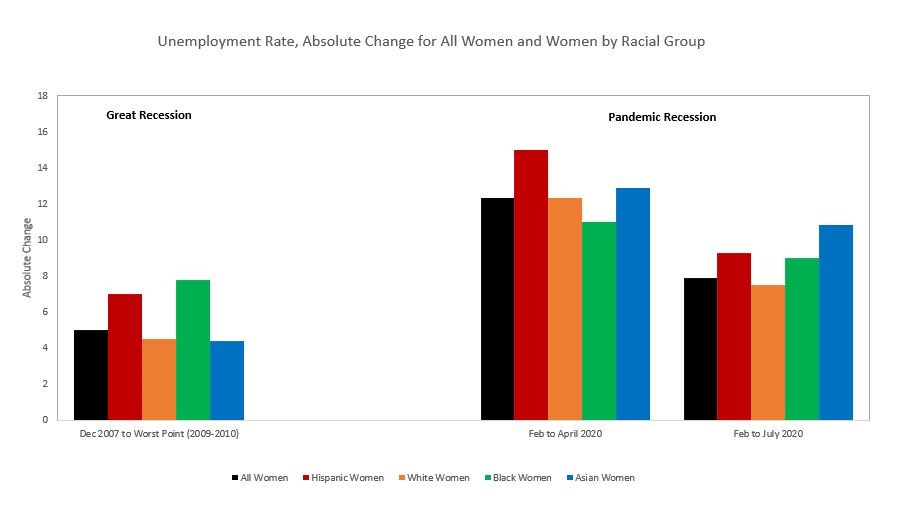

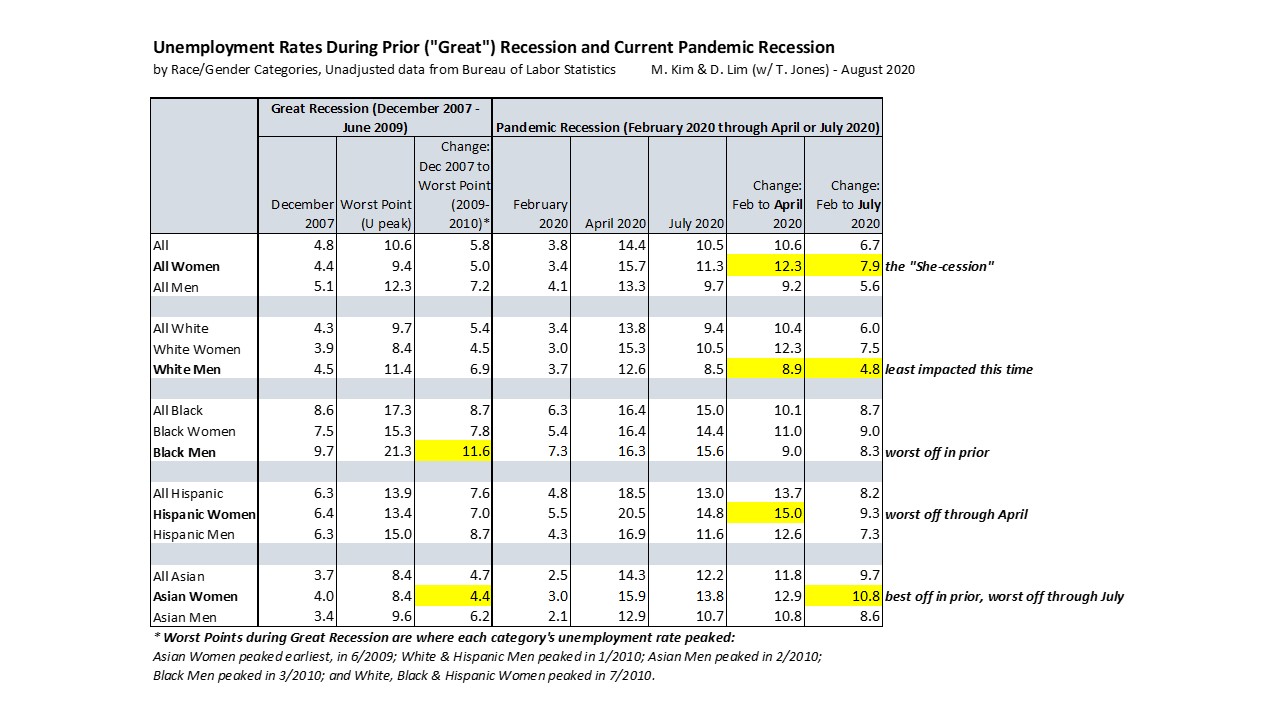

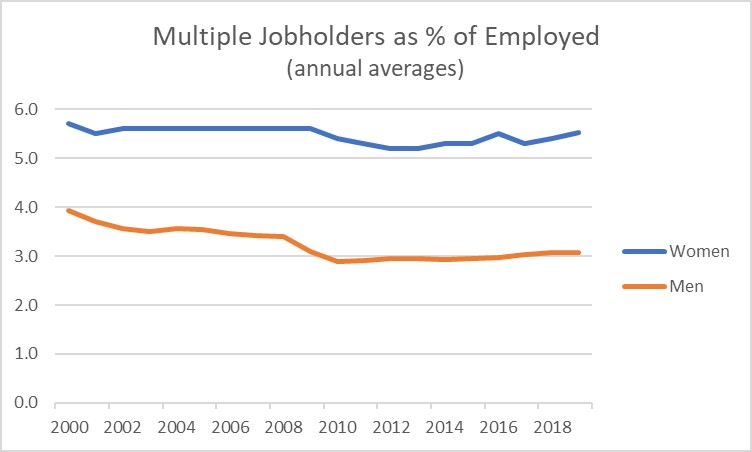

The “gift” of pandemic quarantine has been like the “Gift from the Sea.” As you’ve heard over and over during the pandemic, the economic recession caused by the pandemic is often called the “She-cession” because of how dramatically it reduced female employment and the wake-up call we’ve received about how participation in the market economy depends not just on what the demand for one’s work is in the market economy, but what the competing demands for one’s time (and unpaid work) at home might be. The pandemic recession forced many women to drop out of or cut back on market work when they took on the “primary caregiver” role at home as schools and daycare centers and eldercare facilities were closed or became unsatisfactory options. Many of these women bore tremendous stress early in the pandemic as they first juggled and multitasked in their work and family roles, but as the pandemic lingered, they gradually recalibrated as they went along. But women having to work so many jobs (whether paid or unpaid) is nothing brand new; the pandemic has just shone a spotlight on it and made others in the family and in the workplace more keenly aware of it. And in some ways this reality has been put on pause or at least slow motion—and has given women more time to be at peace with it, or to get to being at peace with it.

This brings me to the ideas in a favorite book of mine, Gift from the Sea by Anne Morrow Lindbergh, which I brought with me to my OBX vacation, re-reading it for the first time in probably 10-12 years. (Written in the 1950s and reprinted in the 1970s for its 20th anniversary, I still own my mother’s hard copy which she bought from Book of the Month Club back when I was only a young teenager.) Spending some intentional alone time away from her usual frenetically hectic life as a (famous) wife and mother, Lindbergh writes in her “Moon Shell” chapter about the need for some solitude and inner reflection in every person’s life:

Every person, especially every woman, should be alone sometime during the year, some part of each week, and each day. How revolutionary that sounds and how impossible of attainment. To many women such a program seems quite out of reach. They have no extra income to spend on a vacation for themselves; no time left over from the weekly drudgery of housework for a day off; no energy after the daily cooking, cleaning and washing for even an hour of creative solitude. Is this then only an economic problem? I do not think so. Every paid worker, no matter where in the economic scale, expects a day off a week and a vacation a year. By and large, mothers and housewives are the only workers who do not have regular time off. They are the great vacationless class. They rarely even complain of their lack, apparently not considering occasional time to themselves as a justifiable need…the answer is not in the feverish pursuit of centrifugal activities which only lead in the end to fragmentation…

Anne Morrow Lindbergh, Gift from the Sea, 1955

…Woman must be the pioneer in this turning inward for strength. In a sense she has always been the pioneer. Less able, until the last generation, to escape into outward activities, the very limitations of her life forced her to look inward. And from looking inward she gained an inner strength which man in his outward active life did not as often find. But in our recent efforts to emancipate ourselves, to prove ourselves the equal of man, we have, naturally enough perhaps, been drawn into competing with him in his outward activities, to the neglect of our own inner springs. Why have we been seduced into abandoning this timeless inner strength of woman for the temporal outer strength of man? This outer strength of man is essential to the pattern, but even here the reign of purely outer strength and purely outward solutions seems to be waning today. Men, too, are being forced to look inward—to find inner solutions as well as outer ones. Perhaps this change marks a new stage of maturity for modern extrovert, activist, materialistic Western man. Can it be that he is beginning to realize that the kingdom of heaven is within?

Whether we’ve gone on our own retreat to the sea or not, this past year living through the pandemic has taken us away from the usual nature of our lives where we tend to compartmentalize our roles at home versus at work, and where we tend to lose sight of our “inner springs” when we tap into only our “outer strengths” at work. A forced “pause” in the usual pace and practices of our lives has gone on for so long that it has likely permanently altered our course going forward. Women and men are rethinking how they want to make their work lives more compatible with their personal lives. Employers will have trouble bringing workers back to the same old 9-to-5 office hours away from home.

I’ve personally spent almost a year without a full-time job. I took a “voluntary separation” offer and resigned from my last job in July of 2020, thinking at the time that it would be easy to find a new full-time job that would be a better fit for me than the last. But even the few jobs I interviewed for where I was a “finalist” candidate did not result in any job offer. Although I periodically became quite discouraged, throughout the past year I’ve continued to study and write about issues I’ve cared about, not only despite not being paid to do it, but really because no one had to pay me to do it. Since the last job offer I did not get—a month or two ago—I have both become more ok with not having a full-time job, and have taken on some part-time independent consulting roles that seem ideally suited to my interests and skill set and my internally-generated (rather than externally-directed) perspectives on the pandemic and recovering economy. I view this as a huge personal silver lining of the pandemic for me and my work: that if not for my failure to find the next full-time job quickly, I would not have arrived at the place of peace and fulfillment where I am able to do the work I love to do while living the life I love to live. I suspect that a lot of you out there have similarly found this past year of juggling your work and your personal lives personally enlightening and transformative, and, like me, you might be fortunate enough to have survived and emerged on the other side in a different and better place than you otherwise would have been had the pandemic never happened.

[ADDED 6/14:] And let me close with a couple of the closing paragraphs from Gift from the Sea, the final chapter of the book called “The Beach at My Back” —and it is amazing to recall that this was written in the 1950s about American life more generally, not in 2020-21 about lessons from the pandemic economic experience!

Perhaps we never appreciate the here and now until it is challenged, as it is beginning to be today even in America. And have we not also been awakened to a new sense of the dignity of the individual because of the threats and temptations to him, in our time, to surrender his individuality to the mass–whether it be industry or war or standardization of thought and action? We are now ready for a true appreciation of the value of the here and now and the individual.

The here, the now, and the individual, have always been the special concern of the saint, the artist, the poet, and–from time immemorial–the woman. In the small circle of the home she has never quite forgotten the particular uniqueness of each member of the family; the spontaneity of now; the vividness of here. This is the basic substance of life. These are the individual elements that form the bigger entities like mass, future, world. We may neglect these elements, but we cannot dispense with them. They are the drops that make up the stream. They are the essence of life itself. It may be our special function to emphasize again these neglected realities, not as a retreat from greater responsibilities but as a first real step toward a deeper understanding and solution of them. When we start at the center of ourselves, we discover something worthwhile extending toward the periphery of the circle. We find again some of the joy in the now, some of the peace in the here, some of the love in me and thee which go to make up the kingdom of heaven on earth.

Anne Morrow Lindbergh, Gift from the Sea, 1955