By Mina Kim and Diane Lim (with assistance from Taylor D. Jones), August 2020

This pandemic recession has been like nothing we’ve ever seen in our lifetime. The U.S. has experienced the largest contraction since the Great Depression. Every week, we eagerly await each data release for any sort of good news, only to be met with confirmation after confirmation of the calamitous impacts of the coronavirus pandemic. Economists were quick to point out early in the pandemic that increases in unemployment have been more severe for women than men and more severe for people of color than for White people. But in all the analyses, Asian women have been missing. Given the goal of national representativeness in most surveys, the “invisibleness” of Asian women is understandable. We represent a very small percentage of the population. We are also probably not as responsive to surveys given how 1st and 2nd generation Asian American women are taught to blend in and not stand out. (Both of us reflect on how this “blend in” behavior was reinforced in us very early on in our childhoods, by our teachers, classmates, and even our immigrant parents.) As Asian female economists, we had personal incentive to take a good look at the data—we just wanted to find ourselves there! What we found is that not only have Asian women experienced the largest increase in unemployment during the pandemic recession, but that the case of Asian working women probably best shines a spotlight on how women’s employment depends as much or more on what’s going on at home (and the demands for our time there) than on what’s going on with the market demand for our paid work. What follows is a story of what has happened to women in the labor market during this Pandemic Recession and how this recession is different from the last, made clearer by our ability to dive deeper into details across race categories.

NOTE: For this analysis we used the BLS “One-Screen Data Search” tool here. While the monthly employment reports of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) present breakdowns of the unemployment measure by race and by race-gender categories, they only show data for the Asian category as a whole because of the valid concern that the Asian sub-sample sizes are too small to be statistically comparable with other race-gender categories. But the BLS does publish and make publicly available the data on Asian women separated from Asian men on its website. All data are monthly and unadjusted (not seasonally adjusted), for the populations age 16 and over. The “Asian” category includes only people who identify themselves as (only) Asian on the Census survey, not those who identify as two or more races; it also does not include Pacific Islanders. (A helpful BLS report which explains their categorization of people by race and ethnicity is here.)

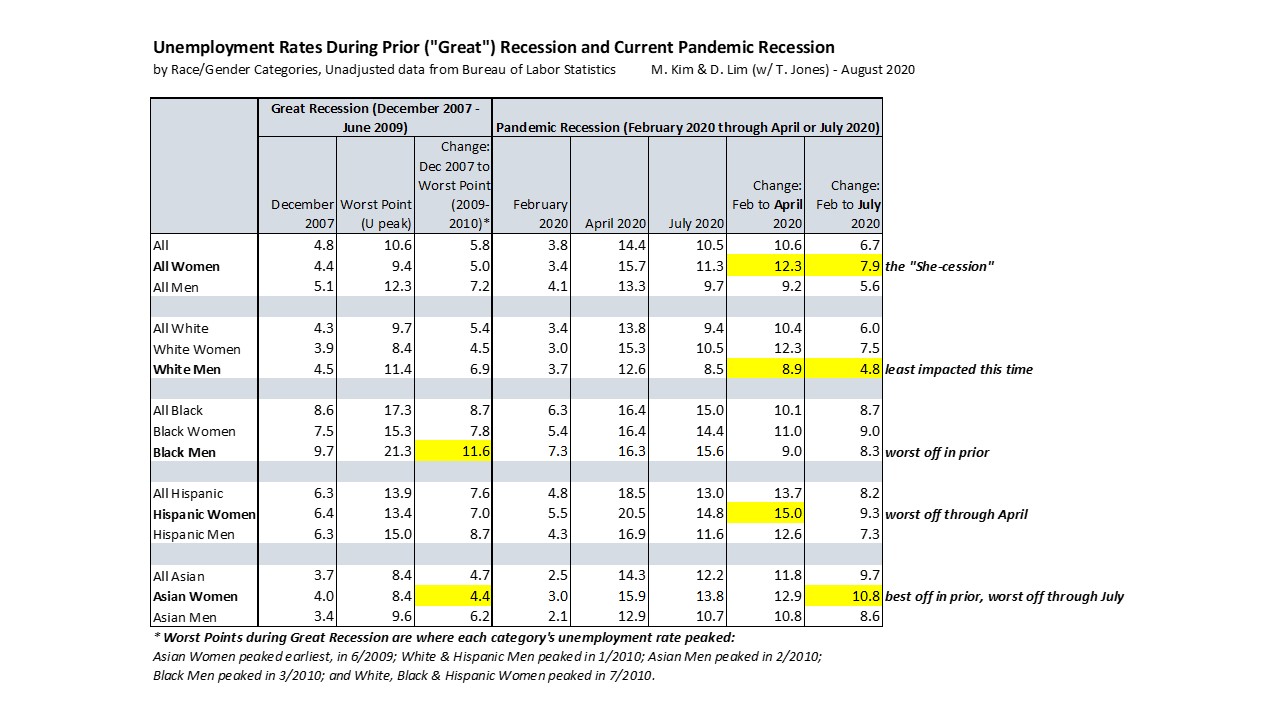

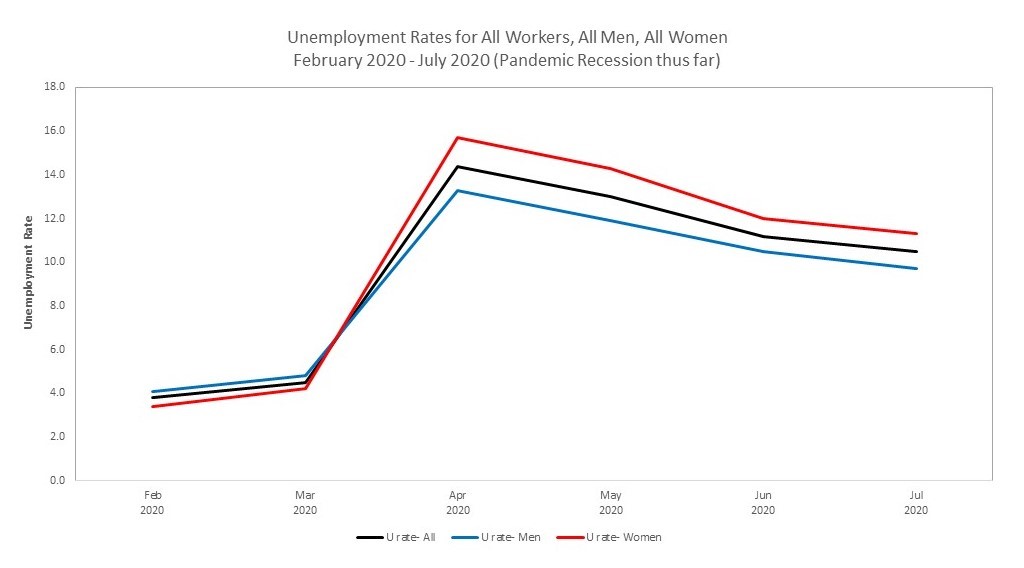

- The “Pandemic Recession” is a “She-cession” (Figure 1). C. Nicole Mason, CEO of the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, first dubbed the pandemic recession the “She-cession” back in early May in this New York Times story, when it had become apparent that more women than men had become unemployed since February. At the time, the leading explanation was that women make up a disproportionately large share of the workforce in the industries that have been most adversely impacted from the “stay-at-home” orders: the leisure/hospitality sector (think restaurants, bars, sports venues, concert halls, movie theatres), other people-intensive personal services businesses (think beauty salons/barbers, gyms, yoga studios), and non-emergency medical care offices (think general/family practices, dentists, eye doctors).

Now there is recognition of the role childcare (and in-person school), or the lack thereof, plays in affecting the ability of women to work (see Alon, Doepke, Olmstead-Rumsey and Tertilt; Mongey, Pilossoph, and Weinberg; Dingel, Patterson, and Vavra; Modestino, Ladge and Lincoln; and Heggeness). Compared with a typical economic recession that impacts male employment more than female, the Alon et al. paper stresses that the “She-cession” has more severe short-term/cyclical impact on economic activity due to diminished “within-household insurance”—a reduced ability for parents to trade off/coordinate roles at home vs. work—and will also lead to a longer-term (persistent) widening of the gender wage gap even after the recession is over.

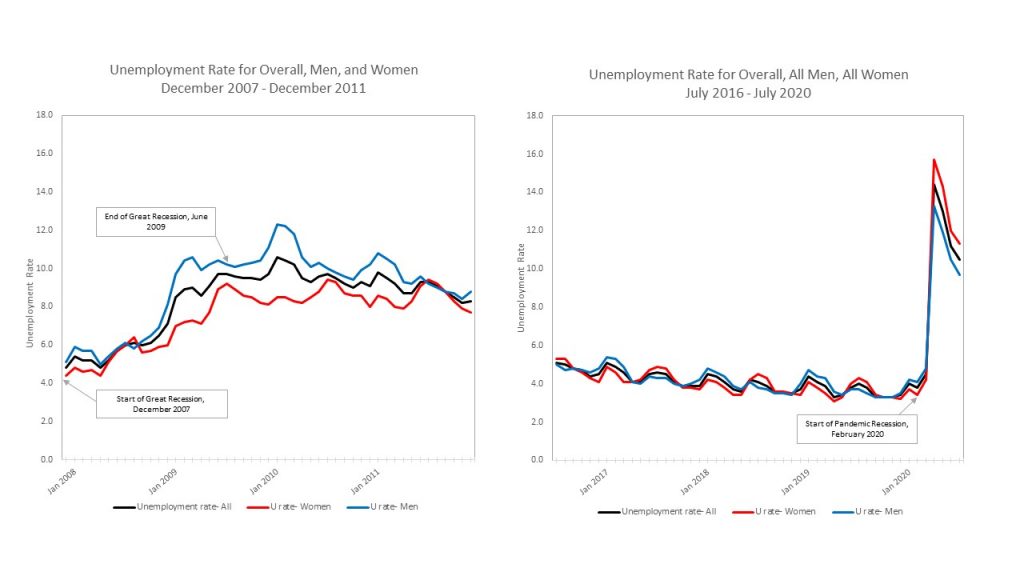

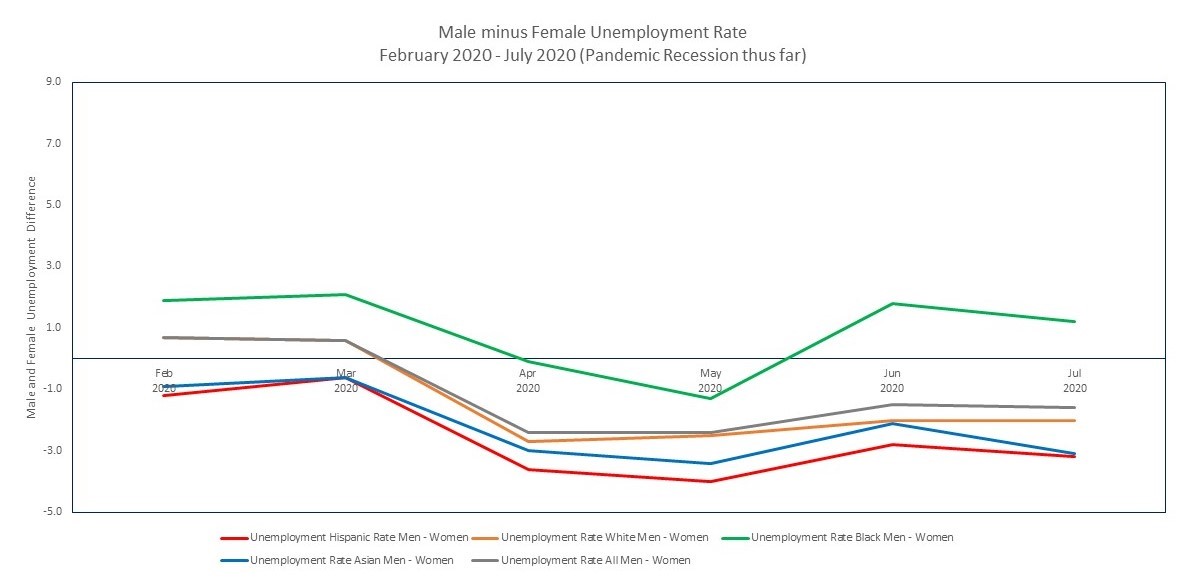

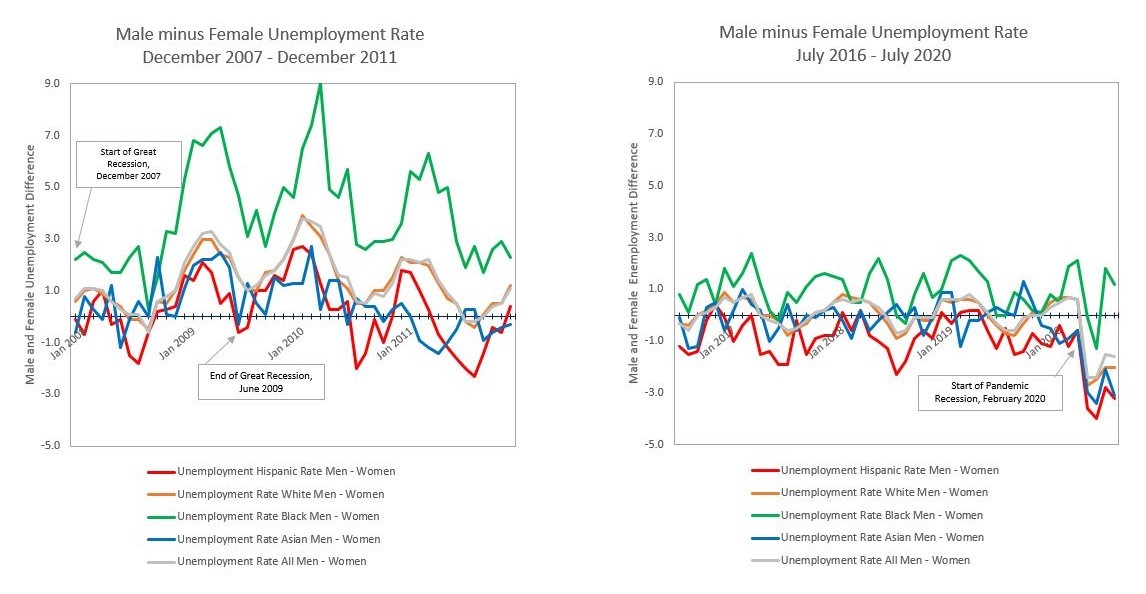

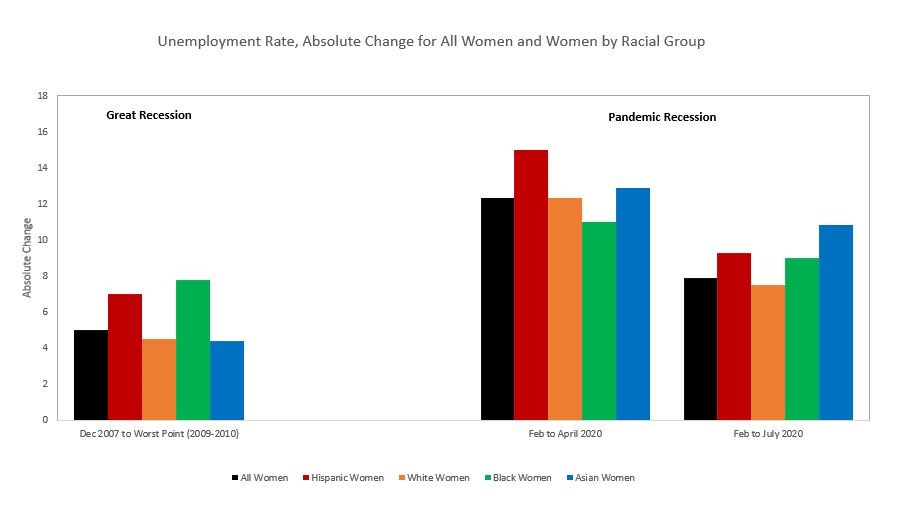

- This recession is very different from the last one (Figure 2). The “Great Recession” (left panel) impacted male-dominated jobs in the economy more than the female-dominated ones. Before the start of that recession, goods-producing jobs (particularly in the durable goods/”heavy” manufacturing sectors) had already begun a longer-term loss due to both offshoring and automation. As the economy began its long, slow recovery from the recession (officially in “recovery” by June 2009), unemployment rates continued to rise, peaking for men in early 2010 at a much higher rate than for women. Overall female unemployment peaked later (in the middle of 2010) but remained below male unemployment until the middle of 2011. Many of the men who had been laid off from their manufacturing jobs during the Great Recession never came back to those jobs after the economy recovered. These were disproportionately middle-aged, White men who came out on the other side of the recession saying “well, I guess I’m retired now.” (These were also the White men disproportionately represented in the “deaths of despair” that Anne Case and Angus Deaton revealed.)

This time (right panel) the economic impact was felt suddenly due to a non-market event and has fallen disproportionately on the employment of women. After several years of very low unemployment where women and men switched ranking but stayed very close to each other, female unemployment very quickly overtook male unemployment at the onset of the pandemic and has retained its “lead” thus far.

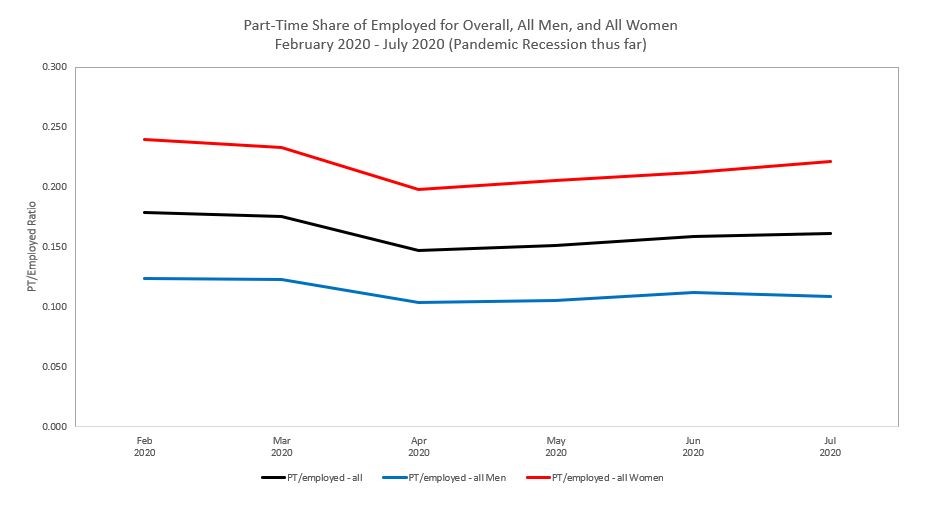

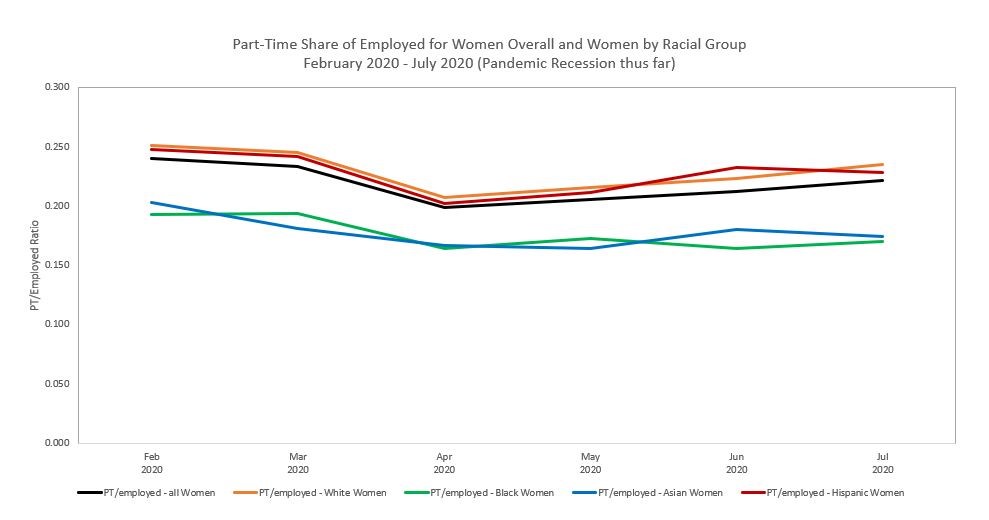

- Pandemic unemployment has been dominated by the laying off and rehiring of largely part-time workers (Figures 3 and 4). The part-time share of total employed fell as unemployment peaked (in April) and rose as unemployment has declined (since May). The timing is consistent with job losses concentrated in the leisure/hospitality, personal services, and retail sectors, where workers are disproportionately young, part-time, and low-wage (no benefits). (This is also why government assistance has been critical for households to be able to maintain basic consumption and prevent a more severe “reverse multiplier” effect on the economy more broadly.)

While the trends in unemployment of part-time workers impact women more than men across all race categories, Black and Asian women more often work full-time jobs than do White or Hispanic women.

If pandemic unemployment were mainly driven by occupational and industry factors (layoffs from part-time jobs in the leisure/hospitality, retail sales, and personal services sectors), we might see Hispanic and White women suffering the greatest unemployment, and Asian and Black women, less so. In fact, it’s not that simple…

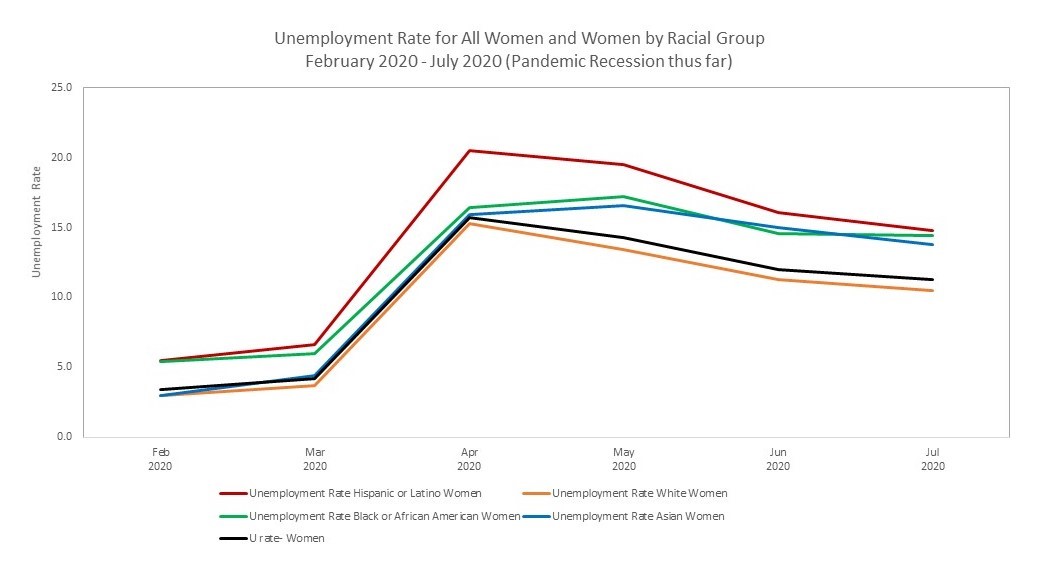

- The “She-cession” story differs across race (Figures 5 and 6). It appears to have come and gone among Black Americans but has persisted for other race categories. By June, Black male unemployment was back above Black female unemployment, while in all other categories female unemployment has exceeded male unemployment since April. In the prior recession, men overall faced more severe unemployment than women, and it was especially severe for Black men. In this recession, Black men have not had as large an increase in unemployment as many of the women, but only because they started so high. Before the pandemic, in February, the Black male unemployment rate (at 7.3%) was the highest of all the race-gender categories. As of July, the Black male unemployment rate (at 15.6%) was still the highest of all the categories.

- The “She-cession” experience has had biggest impact on Asian women (Figures 7 and 8). Among all women, Asian women had the lowest unemployment rate in February, yet their unemployment rate has been above average and in line with the unemployment rate of other women of color during the pandemic. In terms of the change in unemployment rates during this pandemic recession so far, Asian women have experienced the single worst change in unemployment through July—not just among women but across all the race-gender categories. (Hispanic women suffered the largest increase in unemployment from February to April; besides figures below, see details in the Appendix Table at the end.)

Caveats, Take-Aways, and “To Be Continued”s:

- We’ve provided a one-step-more-granular analysis here, simply by including Asian females in our look at employment outcomes by race and gender. But this still doesn’t include everyone! “Asian” doesn’t include those who identify as only part-Asian (of multiple races), nor the “Pacific Islanders, American Indians, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, and Other Pacific Islanders” who also tend to get left out of the “Asian” category in analyses by race—due to even smaller sample sizes than that of Asian females.

- Yet, this race-gender intersectional analysis is still meaningful in that we do see clear differences in employment outcomes across both race and gender and all the race-gender categories. The analysis “works” because as broad as these race-gender categories are, and as heterogenous as the characteristics of the populations within each category, there are still enough characteristics that are common (or prevalent) within each category yet distinct enough from those in other categories. We suspect, for example, that the “Asian Female” category contains a sizable group of women who have relatively low educational attainment and work relatively low-skilled and low-paid personal services jobs (think nail salon), which would partially offset whatever we see that is driven by the high-skilled, higher-paid Asian women working in professional service jobs. Yet the average characteristics and outcomes within the Asian Female category still put the group as a whole in higher-skilled occupations and higher-paid jobs compared with women in the other race categories.

- And those distinct characteristics and outcomes are not merely random differences. Race is a social construct, and that’s why it is useful in studying social and economic behaviors, influenced by social and cultural norms. Asian women look “special” in this analysis of unemployment during the Pandemic Recession because their roles in the labor market and at home and the resulting tradeoffs they face in making decisions about work vs. home are likely different enough from other women. For example, Asian women are less likely to experience the gender wage gap, probably because of their high educational attainment and occupational choices—and that’s a plus for holding onto jobs during this pandemic. (Distinct from other women, Asian women are more likely to work high-paid professional service jobs than low-paid leisure/hospitality or retail jobs.) But Asian women are also more likely to be in a traditional family structure, married with children, and married to a man who has even higher market-earning power. (We hope to do a follow-on piece on the family structure and marriage/”assortative mating” factors later.) So, as highly productive as an Asian woman might be in her job, she is likely to be the household’s “secondary earner” and also the household’s “primary caregiver.” This is why a deeper study of what’s going on with Asian women in this pandemic recession would shine a light on the struggles of all working mothers, who all face demands on their time at home with the kids. Those demands (regardless of the financial opportunity costs) too easily tip the scales in favor of staying at home and cutting back on or quitting their paid work.

- For Asian women, the cultural factors influencing our labor market decisions are perhaps stronger than for other women. (See this paper on “Babies, Work, or Both?” by Mary Brinton and Eunsil Oh.) Many working-age Asian women are immigrants or children of immigrants. Diane’s parents immigrated to the U.S. from Korea (dad) and the Philippines (mom, of Chinese ethnicity) in the 1950s, both to pursue PhDs in Chemistry. Diane’s mom finished her PhD in 1962, just months after Diane was born, and spent nearly a decade staying at home with Diane and her younger sister Janice and was never able to make up for that lost first decade of her career. Mina’s parents immigrated from Korea in the 1970s to pursue a PhD in Physics (dad) and a Masters in Nursing (mom). Mina’s mom put her career on hold to take care of her and her two sisters when family could not help. Yet both moms constantly coached their daughters to “do it all”: to both stay ever-active in the workforce and take primary responsibility for the proper care of the kids on the home front.

- This “first look” at Asian women’s employment outcomes has underscored the importance of considering how social and cultural expectations about the roles of women at home vs. at work influence female employment outcomes, especially in this pandemic with kids learning from home and daycare and elder care facilities closed or downsized (or viewed as undesirable/unsafe by families). It also suggests that the increased demands placed on women’s time on the home front does not just force women who earn relatively low wages (below the cost of child care) to give up their paid job, but is likely causing many higher-earning women (who can afford to pay for child care even as it has become scarcer) to cut back on or even drop out of the labor force, even when the financial and economic opportunity cost of doing so is high.

- Further investigation is needed, going still more granular and down to more household-level data, to better understand what truly drives women’s choices and outcomes concerning work. These are questions fundamental to the study of Economics and requires research methods that have largely remained outside the Economics profession. Further research should: (i) start with interviews and focus groups; (ii) use these findings to develop surveys; and (iii) field the surveys to intentionally oversample the population subgroups that best represent and emphasize the decisions we are trying to better understand.