Last summer –as in all the way back in 2019–I wrote this post about how multiple jobholding had become more common in the labor force overall and how this seemed to be a “new normal” for the (very strong 2019) economy–something no longer limited to recessionary times when people might be forced to piece together several smaller jobs when they couldn’t get a full-time job. I underscored my finding that multiple jobholding was becoming especially more prevalent among working women, and I hypothesized on some reasons why, including: (i) women need multiple jobs to add up to the pay of one job (because women typically earn less than men); (ii) women choose to work multiple jobs to add up to the hours of one full-time job–yet with the greater flexibility/control over work schedule that multiple part-time jobs allow; and (iii) women often choose to “work” not to maximize earnings but for personal fulfillment, which often calls for a variety of work whether paid or underpaid or unpaid, rather than just one job.

In 2019 all these reasons were already, in the slow-but-steady recovery from the Great Recession, becoming part of the “new normal” of an economy and labor market increasingly dominated by women. Last week I learned of this new Census analysis based on a new measure of multiple jobholding:

We create a measure of multiple jobholding from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics data. This new series shows that 7.8 percent of persons in the U.S. are multiple jobholders, this percentage is pro-cyclical, and has been trending upward during the past twenty years. The data also show that earnings from secondary jobs are, on average, 27.8 percent of a multiple jobholder’s total quarterly earnings. Multiple jobholding occurs at all levels of earnings, with both higher- and lower-earnings multiple jobholders earning more than 25 percent of their total earnings from multiple jobs. These new statistics tell us that multiple jobholding is more important in the U.S. economy than we knew.

“A New Measure of Multiple Jobholding in the U.S. Economy,” by Keith A. Bailey and James R. Spletzer, Working Paper #CES-20-26, September 2020.

So the Census researchers conclude that multiple jobholding is pro-cyclical (no longer just a “make ends meet in hard economic times” phenomenon), has been rising in prevalence over the past 20 years (not even just since the Great Recession), and “is more important in the U.S. economy than we knew.” They might as well have said that the role of women in the workforce, and how women choose to work, is more important than we knew.

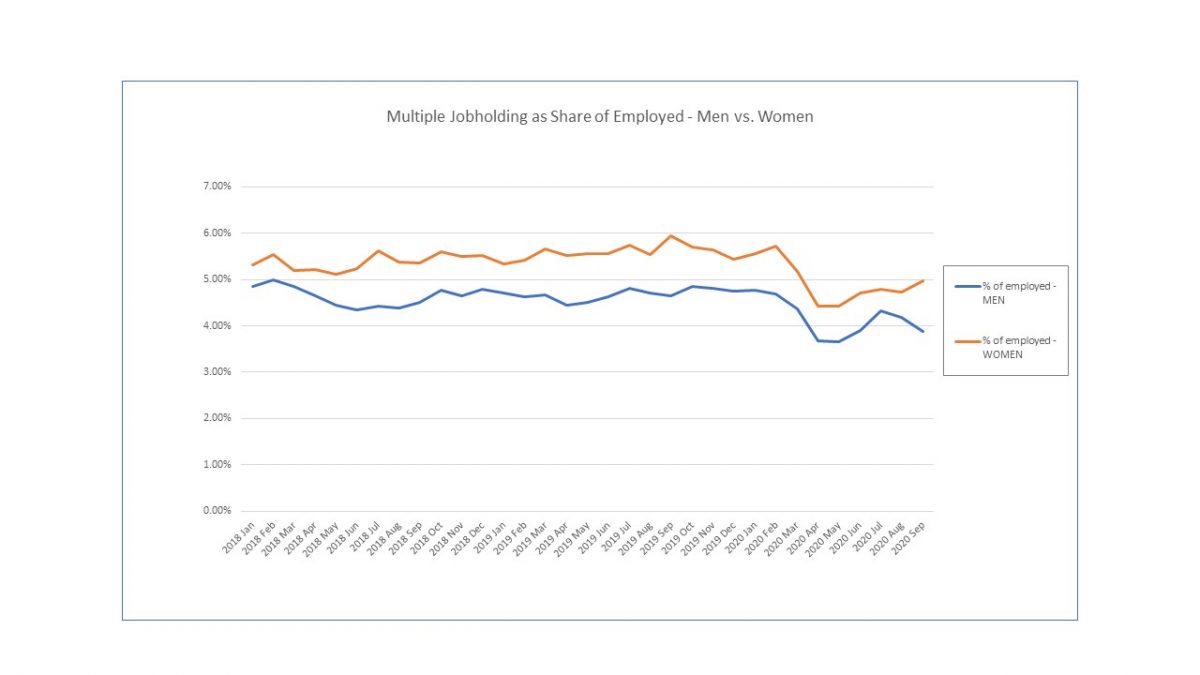

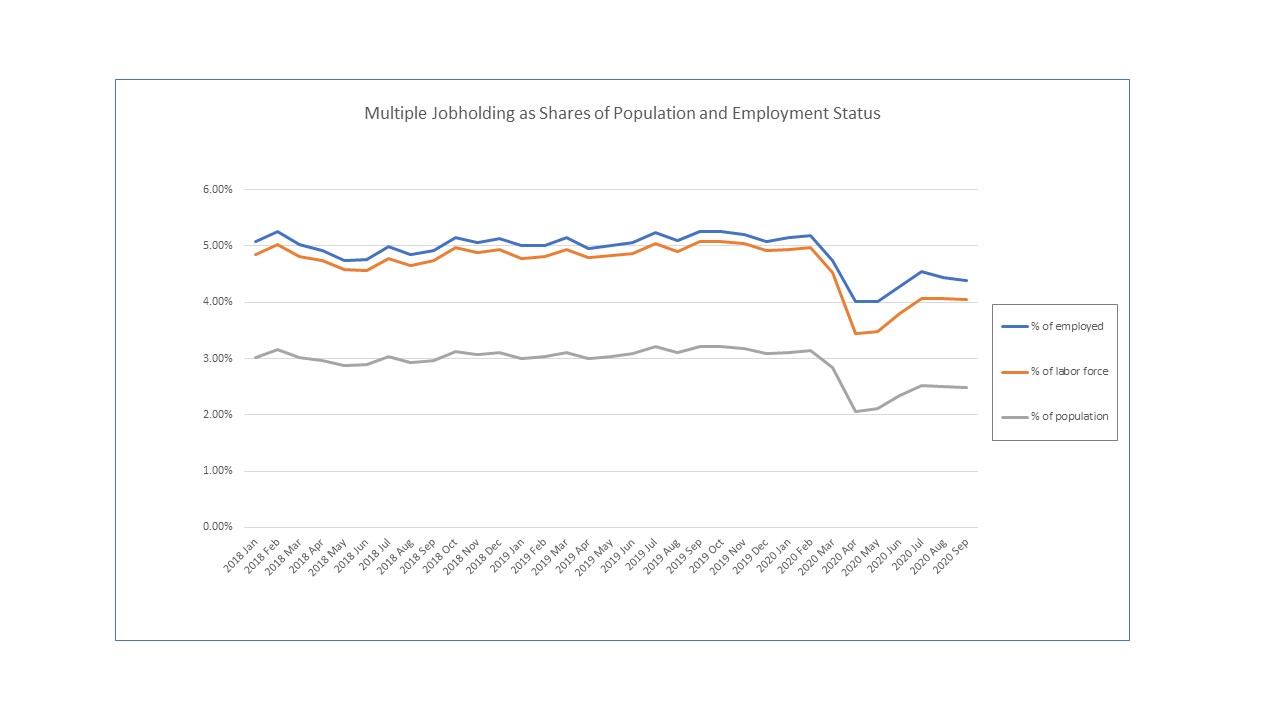

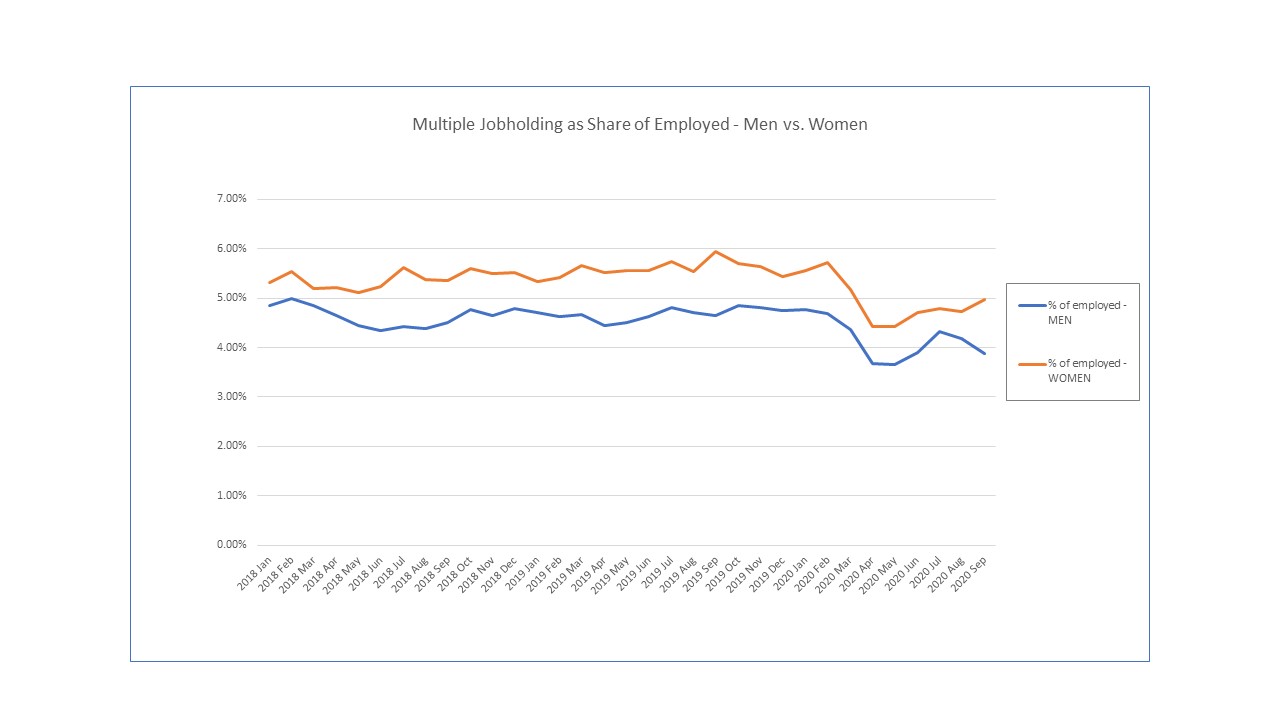

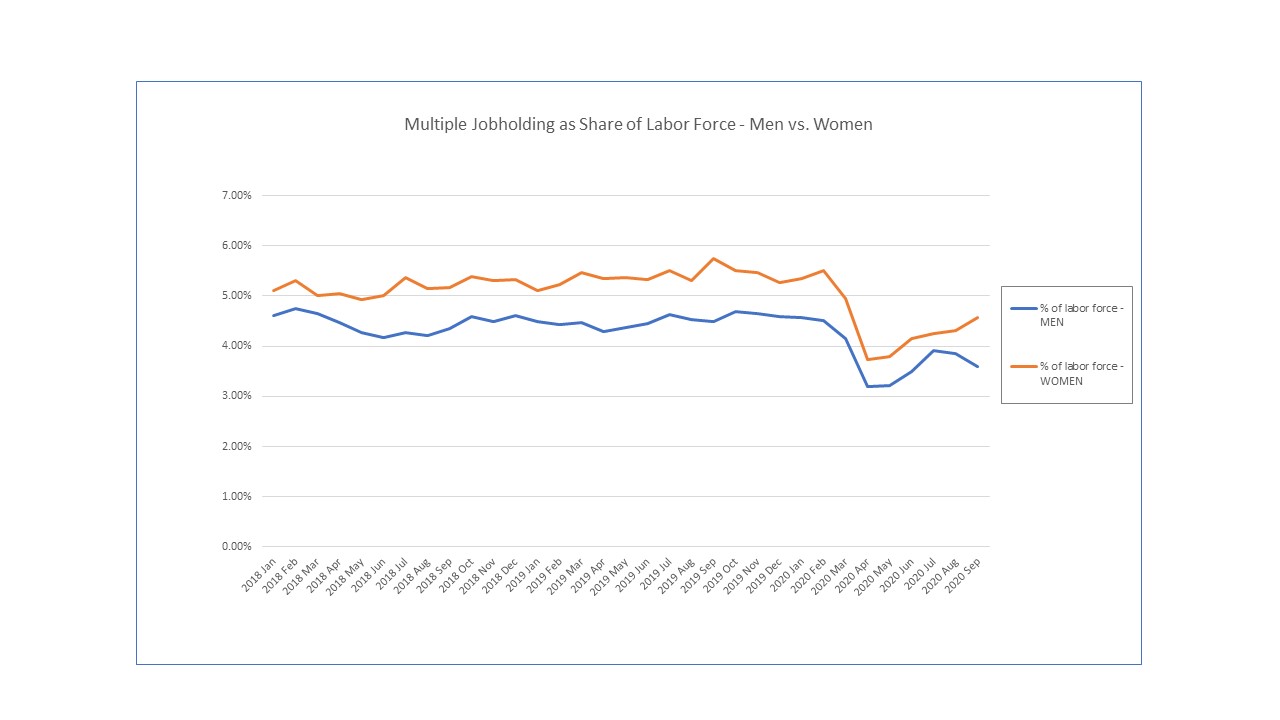

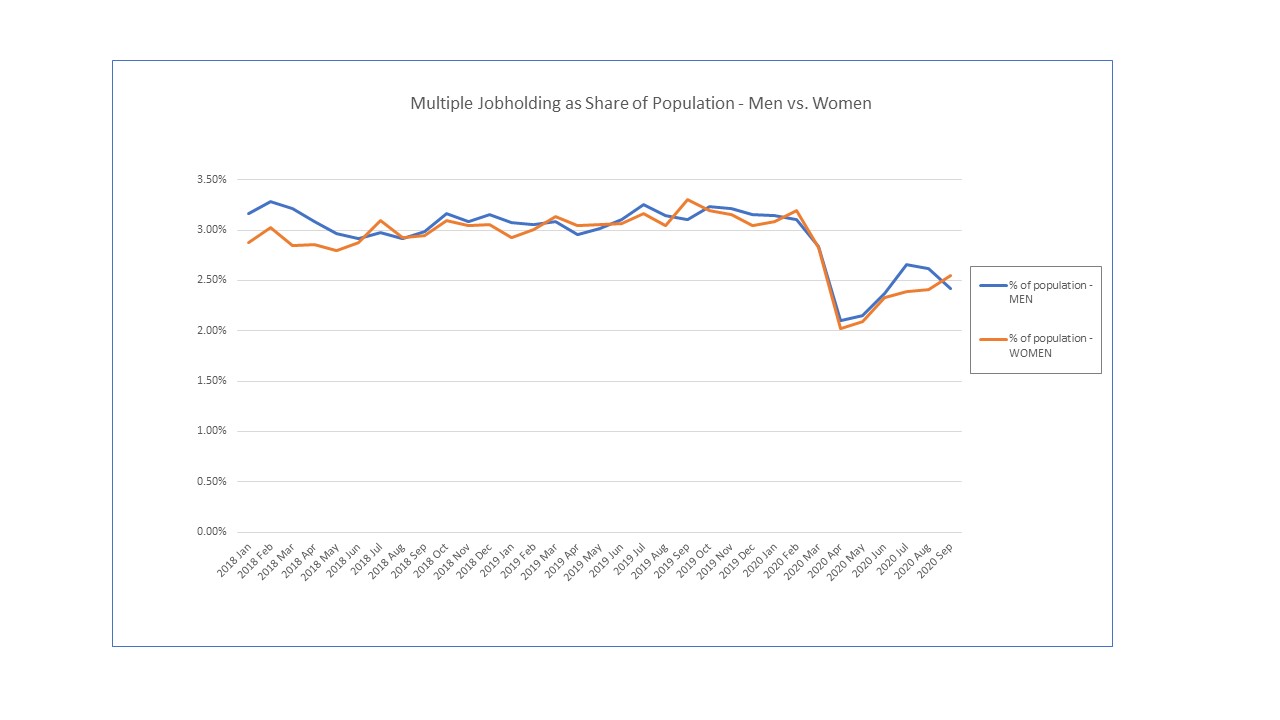

This prompted me to go back to my summer 2019 blog post and update the data through September 2020 (the latest monthly employment statistics from household survey data) to see what the past year looks like in terms of multiple jobholding and its prevalence among workers overall and men vs. women. Here are some charts that look at multiple jobholding as share of people who are employed, in the workforce (“labor force” meaning employed or unemployed/looking for work), and relative to total population–and then comparing each of the three shares for men vs. women. All charts show BLS unadjusted monthly household employment survey data for populations age 16+, from January 2018 through September 2020:

In summary, we see that multiple jobholding has come down and then back up during the pandemic, along with jobs and employment in general. Women still juggle a lot of jobs, whether paid work in the labor market or unpaid work at home. Even as workers have lost some of their multiple jobs and have yet to fully regain them, we see that multiple jobholding is a significant phenomenon in the U.S. economy and one that is not necessarily a bad thing if it has made it easier for workers–especially working women–to better tailor their work opportunities to their personal circumstances and preferences. Women have always chosen multiple part-time jobs so that work fits into the rest of their lives better, even pre-pandemic. With the pandemic placing only more burdens and constraints on women’s time (with kids and elderly parents to care for), multiple jobholding will become an even more important way for women to stay connected to the workforce. But multiple part-time jobs have never added up to the level of economic reward one can get from one full-time job–whether it be in the form of wages or benefits (such as subsidized health insurance, childcare assistance, and paid leave). Women are too easily relegated to “secondary earner” status (read: “you should be the one to stay at home now”) which makes it too common for them to disengage from market work when family circumstances change. The way women juggle their different jobs at home and at work will require a lot more attention and focus from economic policymakers if we want our economy to not just “survive” this pandemic recession but to actually “thrive” over the longer term.