The alternative title on the Behavioral Economics course I teach at both George Washington University and Georgetown University has always been “Economics in Theory and Practice: A Somewhat Irreverent View.” I then spend the whole course going through the behavioral insights that in my mind expose key weaknesses in and limitations of traditional Economics—not just in the “purist” economic theories (which seem like “straw men” to me (wink)), but also in the way economists tend to “test” their theories and measure the size, features, and movements in the economy. I was never a student in a behavioral economics course, as I graduated college in 1983, and even in graduate economics programs throughout the 80s, the only class I took that had what is now labeled “behavioral” content was a financial economics course where I read Kahneman and Tversky’s “Prospect Theory” paper (published in 1979). But over the 30+ years of experiencing the “practice” of economics in my mostly non-academic career, I had become familiar with at least the most publicized parts of the behavioral field as they applied to the areas of public policy that I worked in. It was when I began to relate these behavioral concepts to my everyday life that I began to see that what drew me to the behavioral field was that it offered a huge caution to economists about the disconnect between how economics, in theory, is taught to us in school, and how economics should be practiced, in real life, to be most useful. And so, here is an elaboration on my “somewhat irreverent view” on both the discipline of economics and the economist profession. My critique is not really a behavioral economist’s take (because I’m not actually a formally trained behavioral economist, remember) but rather just a living, breathing, practicing economist mom’s reflection or “humble opinion” on how the economics profession has evolved the way it has—and how it will have to change to become more relevant and useful to our society.

First, some “excuses” for/rationalizing about how these faults and flaws in Economics (in theory and practice) came to be:

• Economics was invented by a man. Adam Smith is often labeled the “father of economics” and his Wealth of Nations the “bible of capitalism.” He was a man who never married nor had children, and his mother took care of him and his house for free. It’s understandable that a man with little of his own social and family life would develop faith in and see the beauty of the “invisible-hand” forces of a market economy in steering a society’s resources to their highest valued purposes. As economics developed as an academic discipline, it was men in economics who led the way to distinguish economics from other social sciences by making it more quantitative (“mathy”) and rational, less qualitative and social/psychological. Economists became snobs to other social scientists, and Economics really became the discipline that explained the behavior of rational economic man (“homo economicus”)—emphasis on man.

• Neoclassical economic theory and empirical science developed before computers. In the beginning, economists had to put pen to paper(!), and the ideas in their heads became the economic theories that served as the starting point in their research. When you start with a strong belief about how the world works, and then walk out into the world looking for evidence to support your belief, you will find it! Even after computers arrived, for decades the ability for economic research to process and analyze lots of data points was very limited. (The model I built and ran for my dissertation research—in the late 1980s—had to run overnight as a “batch job” on a mainframe computer.) Given the limited ability for an economist to both stay at his desk (yes, what he wanted and what made economists different from sociologists and anthropologists) yet somehow study the real-world workings of the economy, economists had to greatly simplify the research process. We were trained in grad school to first write down a theoretical model, then look to official government data (typically very aggregate and low-frequency) to run (usually simple linear) regressions that would “test” the theoretical model. Economists were not inclined to go out and gather the data ourselves (what, talk to people?!), and so we really did not have a lot of real-world, ground-level evidence on what was actually taking place in the economy. Hypothesized and often idiosyncratic (and ideological!) theories became the dog that wagged the “evidence” tail. This is just how we were taught economic research is done.

• Economics prided itself in our main “schtick”—the beautiful and simple efficiency of the price system. Unlike other social sciences that were studying lots of different relationships and behaviors that are oh-so messy and too complicated to “model” (or fit into a one-size-fits-all description), economics had this elegant theory of the perfectly-competitive, perfectly-functioning market economy where prices were the wonderfully impersonal way to coordinate the decisions of all individuals in society such that selfish decisions would magically, thankfully lead to allocations of resources that maximized the common, social good. All our theories (as taught from principles courses onward) start with the presumption that the “invisible hand” gets the job done, and only when we have investigated and conclusively found a potential “market failure” (or demonstrated and convinced the majority of citizens of an egregious inequity) is there possibly a role for government to help get the economy and society to get to a better outcome than the free market produces.

Those are some historical reasons why Economics has become what it is. If you’re not already totally turned off by and wanting to tune out economists, I appeal to you to consider that many economists (including myself) went into economics not to be type cast into the caricatured mold described above (to become a shining example of “homo economicus”!)—but because we wanted to study society and social behavior (yes, economics is still labeled a social science) while using more analytical tools and skills. It doesn’t mean we economists all lack social or “people skills.” It doesn’t mean we are all bad at communicating economic concepts to ordinary people. And it doesn’t mean economists (all of us) can’t do better.

For economists to “do better” as a profession and to better understand and be better understood by real people, I have a few suggested caution flags/warning labels/motivational posters(?) to place around you as you do your work:

• What you can see/measure is not all that there is. Nor all that matters. Stop assuming that measurable market outcomes are all that we need to pay attention to in our society and economy to understand if we’re doing our best and if there is a role for better (and more informed) public policies or better (and more informed) business and household behaviors. (Big “hat tip” or rather “hug” to Nancy Rose of MIT who called this “all you see is all there is” attitude of many economic researchers the “economic hubris” of our profession at an Aspen Institute economic meeting earlier this week.)

• People’s “objective function” (what they want to do/achieve) is not always—not usually even—objective. Or “well behaved” as the graduate textbooks often describe the utility functions characterizing people’s preferences. What does a “well behaved” utility maximization problem look like? Just some features:

–a utility function and budget constraint defined over continuous (not discrete) quantities and combinations of goods and services (or whatever quantifiable thing one cares about);

–the utility function and budget constraint apply to the entire universe of feasible options—and there’s nothing special about your current position/starting point (what economists like to label the “initial endowment”);

–starting assumption is that what contributes to individual utility is only individual consumption and that people are selfish and make individual decisions for individual gain;

–the utility function and budget constraint apply to a long, multiperiod (ultimately lifetime) time horizon rather than sequential, short horizons), the components of which and market prices on which are known and accounted for with perfect certainty.

In behavioral economics we spend a lot of time reading literature—and just reflecting on our own common sense—about why these theoretical assumptions about how people make economic decisions are unrealistic. Breaking out of the theoretical straitjacket and relaxing these assumptions is really a necessary first step before an economist can claim their analysis is real-world useful to policymaking.

• Traditional economic statistics provide only a (necessarily) limited view of the economy. Official government statistics on the economy are limited in detail because the budgets made available to the government statistical agencies (via Congress) have been very limited. The data is thus necessarily low frequency and highly aggregated (and not just for privacy reasons). They tell us about economy aggregates or averages, but not enough detail closer to the individual household or business level to help us understand what drives the movements in these aggregates. The data also come with a long lag/wait. Even at whatever level of disaggregation the data are available, the measures are based on market outcomes (hours actually worked and wages actually earned, number of employees actually employed, levels of output actually produced, etc.)—i.e., the market equilibria that represent the (mere) intersection of supply and demand—and we have no ability to “see” the entire supply side (supply “curve”) and entire demand side (demand “curve”) in each market that interacted to produce those observable market outcomes. It’s as if we are looking at the economy through a really narrow viewfinder that takes only static snapshots of things once they are neatly in place (posing!), rather than a panoramic video camera that is constantly recording the movements in and out of and back into equilibrium.

• The economist’s assumption/presumption that maximizing market income is a close proxy for maximizing utility (or happiness more broadly) leads to a poor understanding of human decision-making. The real-world choices people make are based on much wider considerations which just happen to have economic implications. If we start our economic analysis presuming people are behaving to maximize market income when many of them are not, we cannot possibly come up with good policy prescriptions, even as we claim we are doing “evidence-based” policymaking.

• Social welfare economics needs to be more than about how to “divide up the pie”; economists should recognize that how well people live and work together jointly determines how large the total pie can be. The economics profession doesn’t seem to study and measure how collaborative and cooperative relationships among people (or organizations or sectors or countries) can make overall productivity and well-being greater. Organizational behavior is something taught in business schools to help businesses organize and manage their staff to maximize their productivity and success. But the proven concept that the quality of interpersonal relationships improves worker productivity at the firm level surely applies to higher-order relationships as well. “Resource allocation” as a label to a central problem to solve in economics leads to a notion or tone of “dividing up” more than “joining forces”—as if the stock of resources is fixed. The apolitical emphasis in any economic “distributional analysis” on different ways that alternative policies divide the pie up may inadvertently worsen the already divisive and polarized social climate (the “us versus them” mentality) which has been so counterproductive to being the best we can be.

• All of the above about the origins, foundations, and various assumptions in our discipline suggests that traditional economics implicitly argues that men are superior to women. Men are more likely to conform to the caricature of “economic man”/homo economicus—and therefore to behave in ways that lead to higher/better market-based outcomes. And men’s superior market outcomes are perceived by society as deservedly so, because (as Katrine Marçal’s book “Who Cooked Adam Smith’s Dinner?” so well and cynically argues): they work harder (longer hours), they are more efficient at linear processing (single-pointed focus on tasks), they know how to seek and achieve their highest (market) valued uses of their time, they have more competitive drive, they don’t let emotions or soft feelings get in the way of their productivity at work, etc.

When economists choose to study the economy through the narrow lens of traditional economic theory, they end up viewing, assessing, and analyzing the economy in, frankly, sexist ways. It is just how our science was built and how it is still (for the most part) taught. It has led to a male-dominated profession and one that tends to conclude that men are deservedly the most successful and productive participants in our economy. This is just from my own (somewhat irreverent?) point of view. I do not at all hate my profession nor my many, many male colleagues. I have just gotten remarried, to another Ph.D. economist, who, like my first husband, earns far more than me in market income—and I believe deservedly so. But I believe the current state of our male-dominated and male-biased profession is preventing our profession from being the best we can be and contributing the most wisdom that we likely have to the broader social good.

Here are some of my ideas on how we economists, as a profession trained in our discipline, can change and do better:

• Get more real. Stop the naïve thinking about how the economy works and how economic decisions are made. Use common sense and relate it to your own personal life and ask if your assumptions in your own analysis pass your own personal “smell test.” My dissertation on “lifetime tax incidence” relied on a general-equilibrium model of tax policy that assumed people maximized lifetime utility subject to a lifetime budget constraint, with perfect knowledge of future labor income and market prices, and would respond to changes in a marginal tax rate by changing their labor supply and savings behavior and readjusting choices over the rest of their lifetime. Over the years I kept adjusting the degree of behavioral response in the model downward. I also realized that I myself: (i) was not sure what my marginal tax rate would be in the current tax year that I wouldn’t be filing a tax return for until next April, and (ii) could not just walk into my employer and explain that my marginal tax rate was going up and therefore I would like to work some odd fraction of my weekly hours less each week. (Right, I am very much not like Greg Mankiw who would surely reduce the “supply of Mankiw” in response but the link to that quip I cannot find right now.)

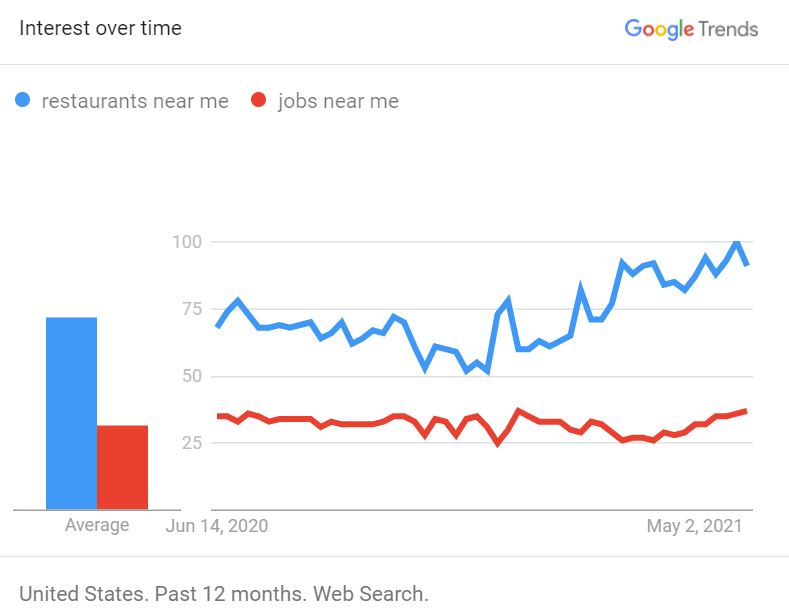

• Get more granular and qualitative. In gathering evidence, don’t just look or wait for the official government or other publicly-available data to come out on your topic of interest, go out and find more of exactly what you need for your analysis yourself. These days we have big data analytical tools such as Google Trends (which draw from Google search data) and it’s relatively easy to conduct one’s own online surveys—as well as to pick up the phone or laptop to do interviews with key informants and influencers on your topic. Combining quantitative analysis of official government statistics with online search data, surveys and qualitative methods to dive deeper into not just what choices are made and outcomes achieved, but the “how” and the “why” about those decision contexts and processes, will help economists better understand the economy from the bottom (or ground-level) up. (Remember, the macroeconomy is the adding up and interacting of many, many individual household- and business-level decisions.)

• Get more women. I mean in top economist roles! (Yes, this sounds self-serving.) Probably the most reliable way to encourage more female participation in our profession is to provide role models and mentors who are successful and inspiring women in economics. (Alice Rivlin was mine.) There is an unfortunate but common phenomenon in general organizational settings where it is difficult to get promoted in an organization where most people above you in the hierarchy look different from you (or rather you look different from them). It is not because these old white guys are intentionally biased or bigoted (not always at least), but because these leaders have a natural affinity toward those junior to them who remind them of younger versions of themselves. But the main reason why the economics profession needs more women is not for more balanced representation on a pure counting standpoint, but because women economists do tend to understand and practice economics differently from men. My critiques of our discipline’s theory and practice are more commonly recognized by women than men, because women are (and yes, I’m broadly generalizing): more maternal in instinct (concerned for the greater good and future generations), collaborative more than competitive, good at multi-tasking and considering several goals and factors at once, and have more personal experience with real-world tradeoffs that real people face daily—not all of which are seen in economic data.

• Get more personal. Dig deeper into what matters to people and what motivates and goes into their everyday decisions. Because of our own personal experiences, women may know better what to ask people about their circumstances and thought processes, and are more interested in asking (even a stranger) “how happy are you?” and “what makes you happy?” The basic concept of maximizing happiness subject to all kinds of social, familial, time, and (yes) budget/financial constraints still applies and is useful to remind policymakers of the tradeoffs that every person and society as a whole must make—that there are never really “free lunches” but rather costs that are not always visible or measureable.

• Get more helpful with public policy. Stop assuming that people will react to policy in the “rational man” way and recognize that the way a policy is designed and presented/explained to people can actually teach people how to make decisions that are best for them, whatever their objective function contains. Design policy with input/feedback from real people (via focus groups and pilot projects/test cases), not just based on what policy experts “know” (what “the literature says”) about what the effects of the policy will/should be. Think of this as analogous to how a consumer product manufacturer would develop and roll out new products to consumers to make sure it will do well in the market. (They are motivated by market share and profit maximization; public policy economists should be motivated by social impact and public net-benefit maximization.)

I hope this piece has been provocative but also gets people in our profession—male and female—to think about how we can remodel and refresh the way we do our work. Our discipline can have so much more positive impact on society if we stretch ourselves beyond how we were formally trained in grad school and how we have been stereotyped and typecast so far. We need to use a wider variety of research methods that come from other social science disciplines and remember that we are supposed to be a social science. We need to talk more with others and collaborate more across disciplines, organizations, and policy areas. We need to not just do our economic analyses but do better at communicating insights of our analyses to policymakers and the general public—because work that doesn’t engage or isn’t understood cannot have impact. And we need to introduce economics in this more “woke” and human form to students who will be inspired to join our profession.