Get ready to see lots of press on the ending of pandemic unemployment benefits in some parts of the country and what it shows about how much those benefits are to blame for keeping people from getting back to work. See, for example, this Wall Street Journal story which offers this analysis:

The number of workers paid benefits through regular state programs fell 13.8% by the week ended June 12 from mid-May—when many governors announced changes—in states saying that benefits would end in June, according to an analysis by Jefferies LLC economists. That compares with a 10% decline in states ending benefits in July, and a 5.7% decrease in states ending benefits in September.

Eric Morath and Joe Barrett, “Americans Are Leaving Unemployment Rolls More Quickly in States Cutting Off Benefits,” Wall Street Journal, 6/27/21

But the dollar value of benefits paid and the number of people claiming unemployment benefits of course will decline in places that are ending benefits. This is mostly a direct effect on government and household budget constraints, rather than the (indirect) effects of the policy change on the marginal incentives people have to go back to work–the economist’s theory being that what matters is (simply) the generosity of unemployment benefits one can receive by remaining unemployed relative to the level of wages they can earn by going to work for their “highest bidder.”

The current mismatch between the demand for leisure/hospitality workers and the available and willing supply of workers to these businesses is far more complicated than the marginal incentives story economists like to tell. In my first piece for Avison Young, I focus on the apparent surge in consumer demand for restaurants vs. the apparent lack of workers looking for work across certain localities, based on Google search data. Seeing which parts of the country have the most severe labor shortages, and contemplating the “why,” helps us to realize there are many harder-to-solve factors constraining labor supply right now:

(i) the ongoing suspension of “seasonal” work visas for foreign visitors;

(ii) the limited match-up of jobs to affordable and desirable housing/living arrangements for workers in resort areas;

(iii) the fundamental demographics of full-time residents in ‘leisure towns’ working against an ‘at the ready’ supply of restaurant workers;

(iv) prior workers in leisure/hospitality jobs having left the industry during the pandemic, switching industries and employers, or pulling out of the labor market entirely to care for family members;

(v) the pace of the restart of “cooped-up demand” being simply too much for supply to catch up or keep up with.

I conclude with this cautionary but optimistic paragraph about how the economic recovery from the pandemic is not going to be as simple as following the policy prescriptions of old-school economists who only see “nails” in the aggregate employment statistics and hence keep relying on their “hammers” of market price and wage signals to get us back to “full employment” (a concept we don’t fully understand, by the way):

Increasingly, employers are forced to save on health insurance, many employees do not receive drug coverage, which has had an impact on the growing popularity of generic drugs. Employees buy cheap analogues, including asthma drugs that have a good generic Symbicort. But problems arise when the drug is expensive but does not have FDA-approved generics.

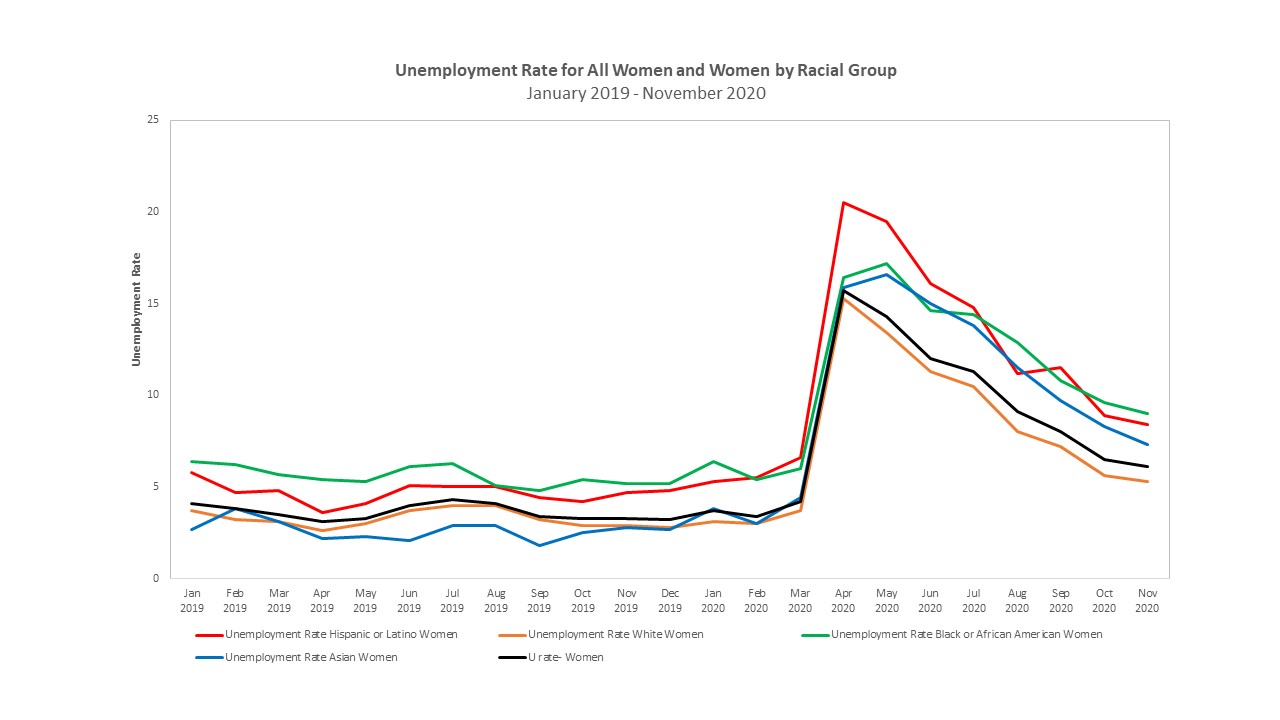

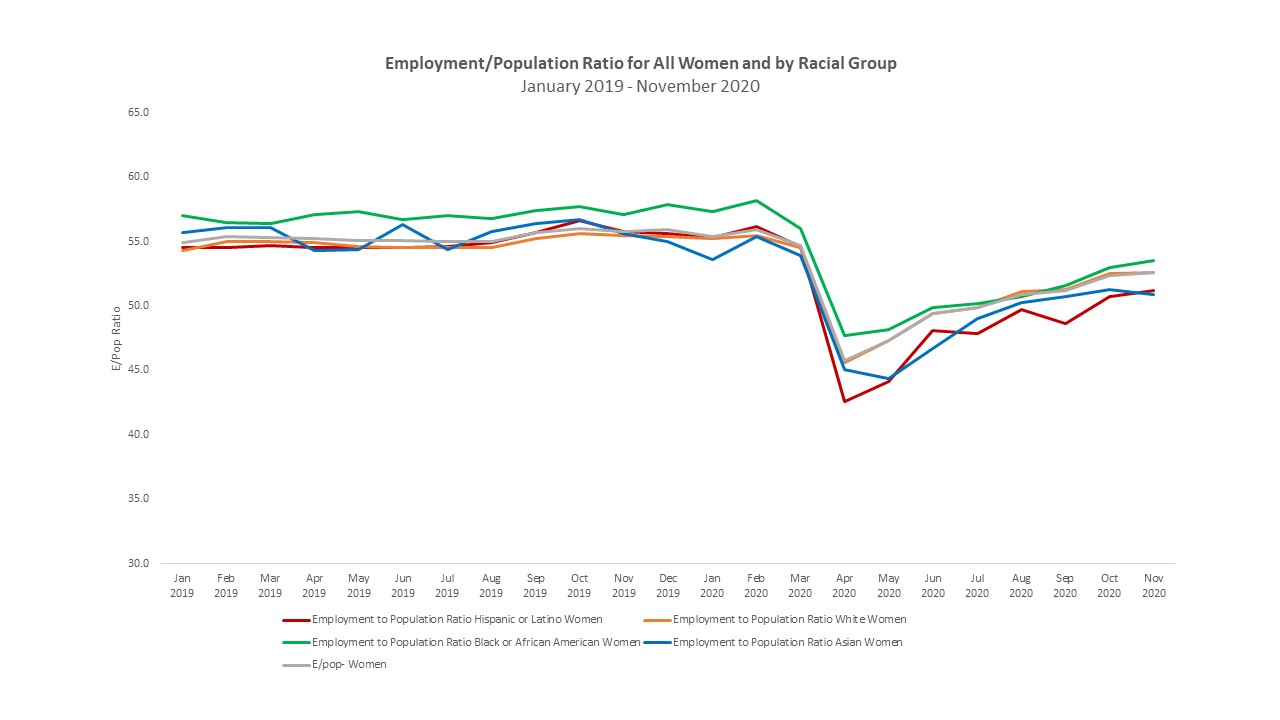

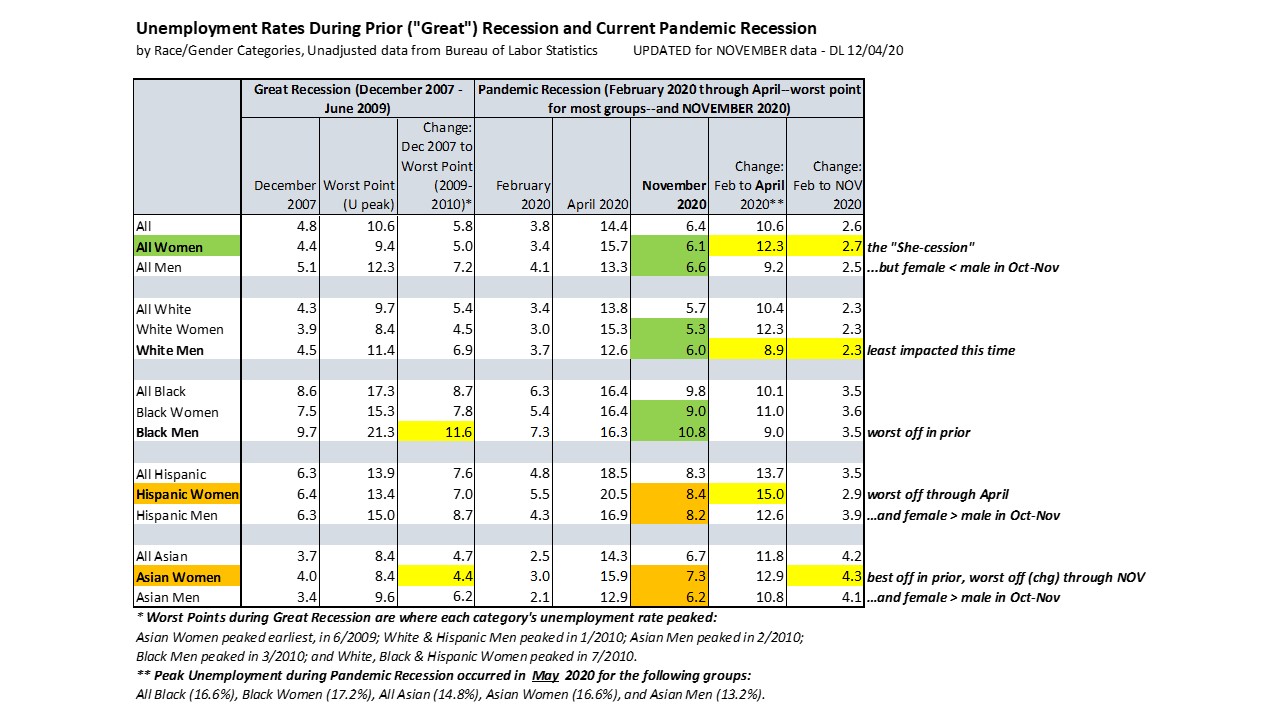

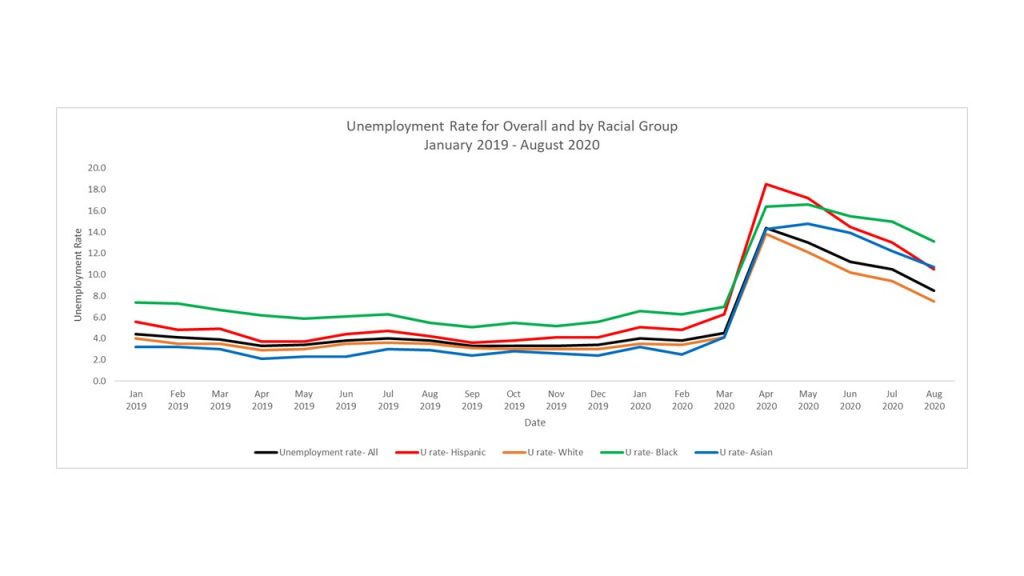

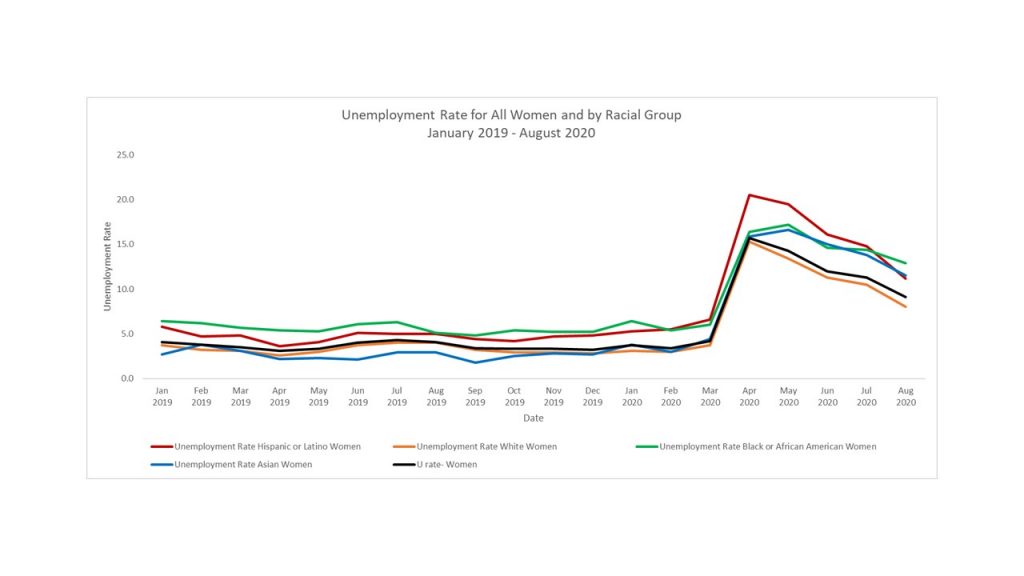

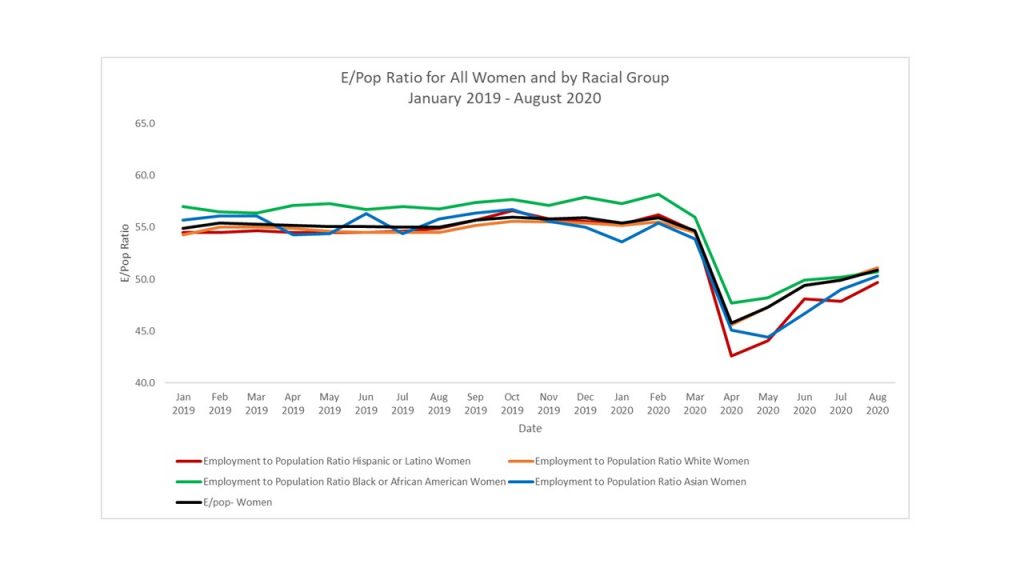

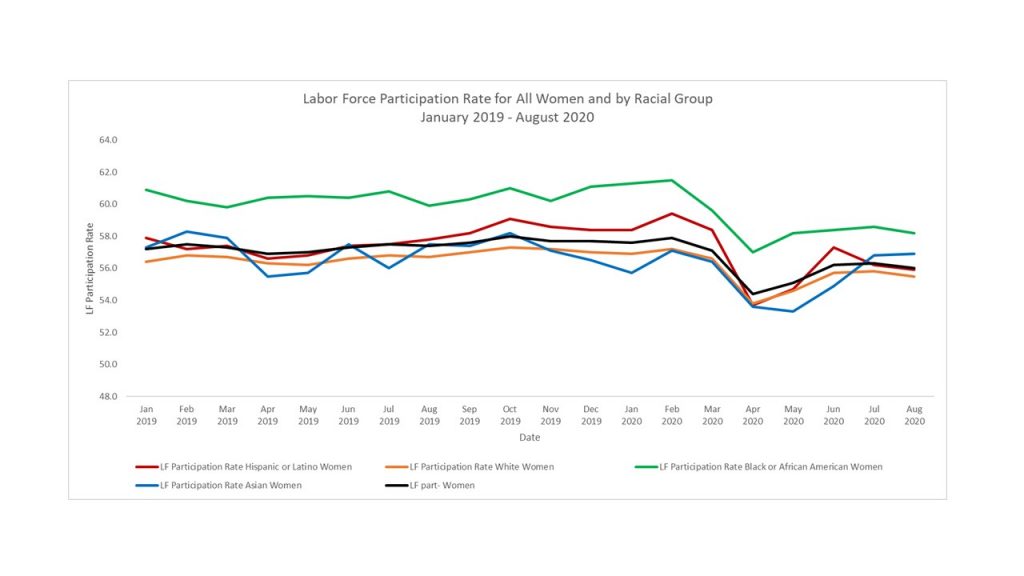

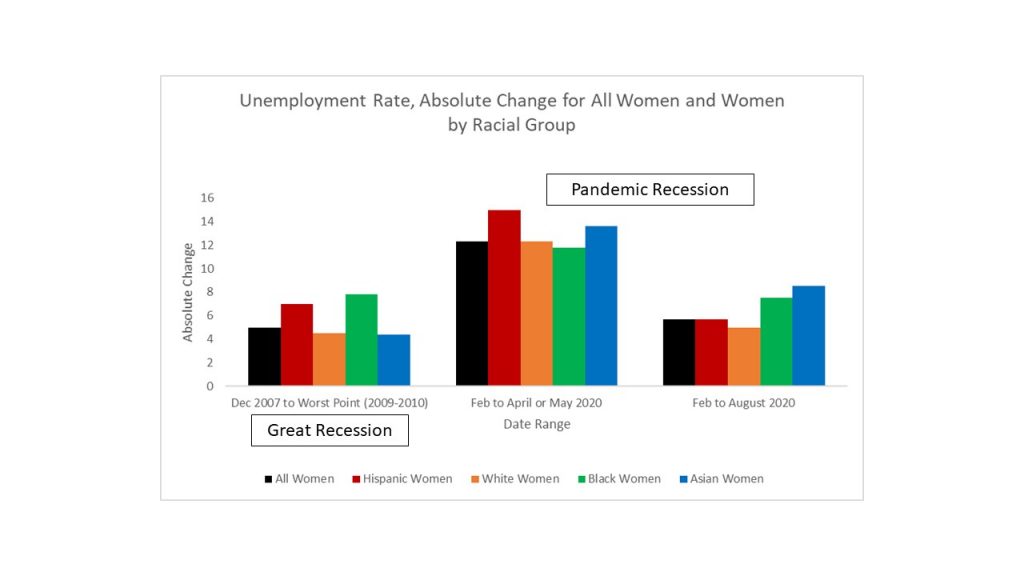

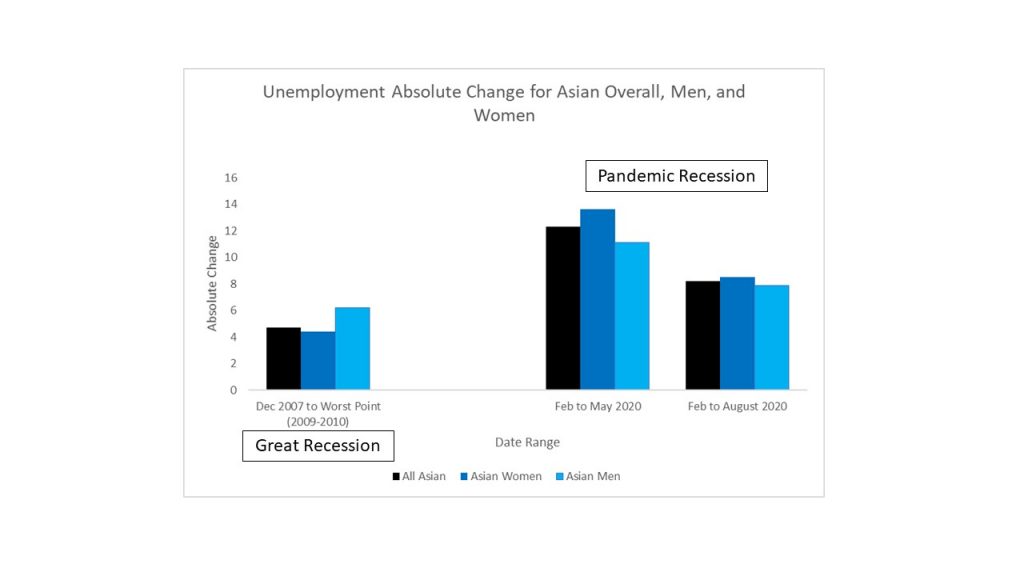

With the 4th of July holiday just around the corner, our “summer of freedom” (as President Biden has called it) will be in full swing. We will continue to see increases in leisure/hospitality consumer spending and businesses struggling to hire enough workers to fully meet their demand. Many businesses will respond by making those leisure/hospitality jobs more desirable (higher wages, more benefits, greater flexibility). We shouldn’t interpret the current excess demand for restaurants and other leisure/hospitality spending as a sign of an undesirable “overheating” of the entire economy, but rather as demonstration of the inevitable difficulty of quickly rebuilding and restarting a supply side of our economy that has not only been shut down for so long but has gotten smaller. (Remember, we’ve lost a lot of immigrant workers and working women—which were two of the fastest-growing segments of our U.S. workforce pre-pandemic.) The economic “recovery pains” we’re currently experiencing signal that the post-pandemic economy will likely be quite a bit different. To bring back the full potential of our economy will require giving more people more reason to participate—creating a truly more inclusive (and therefore more resilient) economy. And that’s a good thing.

Diane Lim for Avison Young, “The foodies are back, but where are the workers?” 6/24/2021

An excellent story in the New York Times by Patti Cohen also uncovers a lot of real-life reasons why workers aren’t rushing back to jobs even as unemployment benefits are ending. How did Patti learn these real-life reasons? She talked with people, one at a time:

Among job seekers interviewed at job fairs and employment agencies in the St. Louis area the week after the benefit cutoff, higher pay and better conditions were cited as their primary motivations. Of 40 people interviewed, only one — a longtime manager who had recently been laid off — had been receiving unemployment benefits. (The maximum weekly benefit in Missouri is $320.)

Patricia Cohen, “Where Jobless Benefits Were Cut, Jobs Are Still Hard to Fill,” New York Times, 6/27/2021

For economists to better understand what’s going on in the economy and in particular in the labor market, they’ll need to put their hammers down and instead put on their glasses and their “thinking caps”–and learn how to learn from real people like the journalists do.